ASK DR. FORMAT by Dave Trottier

CROSS-CUTTING

QUESTION

What is cross-cutting?

ANSWER

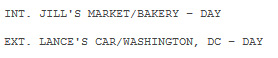

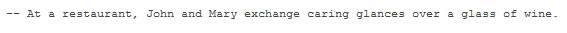

Cross-cutting is an editing technique when the editor cuts back-and-forth between action happening at two different locations. Thus, it is possible to cut back-and-forth between two sequences.

* * *

One reason I recommend that screenwriters read a lot of screenplays is so they can gain a true sense of how screenplays, acts, sequences, and scenes work. Good luck and keep writing!

QUESTION

What is cross-cutting?

ANSWER

Cross-cutting is an editing technique when the editor cuts back-and-forth between action happening at two different locations. Thus, it is possible to cut back-and-forth between two sequences.

* * *

One reason I recommend that screenwriters read a lot of screenplays is so they can gain a true sense of how screenplays, acts, sequences, and scenes work. Good luck and keep writing!

SEQUENCES

QUESTION

What is a sequence in a screenplay? How many sequences will there be in a screenplay?

ANSWER

A sequence is a dramatic unit made up of more than one scene. It is usually about 10-15 pages in length (but can be more or less) and has its own beginning, middle, and end. You can think of car-chase sequences from movies as examples.

Movies are composed of acts, which are composed of sequences, which are composed of scenes. Well, not always…but generally that's true. There is no magic number as to how many sequences should be in a movie. Some movies, by their nature, will have more or fewer sequences than other movies.

SCENES

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

So what's a scene?

ANSWER

A scene is a much shorter dramatic unit than a sequence. Technically, a scene changes when one of three scene elements change: camera placement (INTERIOR or EXTERIOR), location, or time (usually DAY or NIGHT). Those three scene elements can be seen in a master scene heading:

QUESTION

What is a sequence in a screenplay? How many sequences will there be in a screenplay?

ANSWER

A sequence is a dramatic unit made up of more than one scene. It is usually about 10-15 pages in length (but can be more or less) and has its own beginning, middle, and end. You can think of car-chase sequences from movies as examples.

Movies are composed of acts, which are composed of sequences, which are composed of scenes. Well, not always…but generally that's true. There is no magic number as to how many sequences should be in a movie. Some movies, by their nature, will have more or fewer sequences than other movies.

SCENES

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

So what's a scene?

ANSWER

A scene is a much shorter dramatic unit than a sequence. Technically, a scene changes when one of three scene elements change: camera placement (INTERIOR or EXTERIOR), location, or time (usually DAY or NIGHT). Those three scene elements can be seen in a master scene heading:

Most often, people use the term scene casually and seldom refer to a "technical” scene, but to a short dramatic unit that may consist of a scene or several scenes, but not long enough to be a sequence.

Keep writing!

Keep writing!

WHERE HAVE ALL THE COURSES GONE?

QUESTION

Where can I take an online course to learn how to write scripts. [Author's note: Yes, this was a real question asked by a real person. It's not an advertisement.]

ANSWER

Online screenwriting classes abound. Here are just a few places you can go:

Keep writing!

QUESTION

Where can I take an online course to learn how to write scripts. [Author's note: Yes, this was a real question asked by a real person. It's not an advertisement.]

ANSWER

Online screenwriting classes abound. Here are just a few places you can go:

Keep writing!

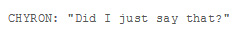

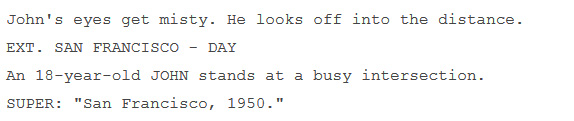

FOR CHYRON OUT LOUD

QUESTION

What is a chyron? [Pronounced kīrän.]

ANSWER

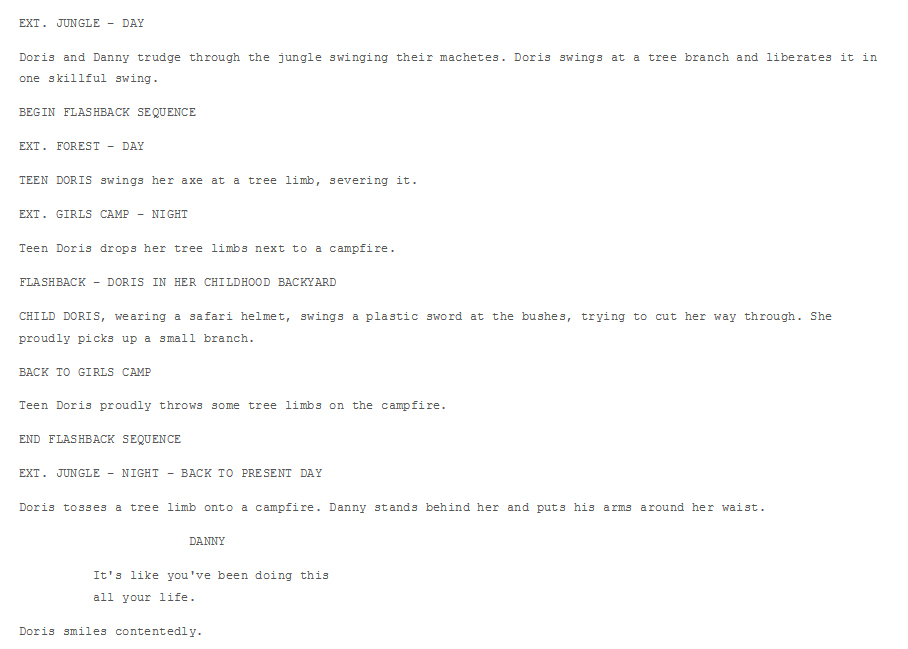

It's the caption superimposed anywhere on a television or movie screen. Thus, it's handled much like a superimposition (SUPER):

QUESTION

What is a chyron? [Pronounced kīrän.]

ANSWER

It's the caption superimposed anywhere on a television or movie screen. Thus, it's handled much like a superimposition (SUPER):

You could also format it as you would a text message, if you prefer.

The term also refers to the text-based graphics that appear at the bottom of your TV during a news broadcast.

The term also refers to the text-based graphics that appear at the bottom of your TV during a news broadcast.

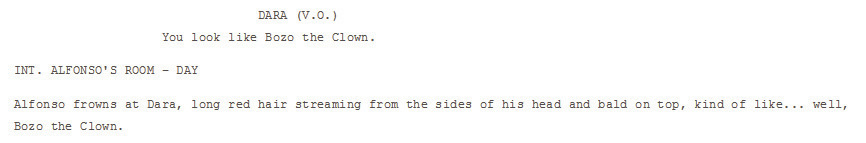

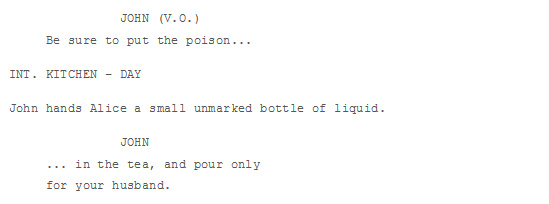

STARTING THE SCENE BEFORE THE SCENE

QUESTION

I am at the end of a scene and have a character from the upcoming scene who says something before we cut to that scene the character is in. How do I format that?

ANSWER

There are two ways, and I'll illustrate with two examples. In the first, use a voice over:

QUESTION

I am at the end of a scene and have a character from the upcoming scene who says something before we cut to that scene the character is in. How do I format that?

ANSWER

There are two ways, and I'll illustrate with two examples. In the first, use a voice over:

As you can see, Dara's line is actually said in Alfonso's room, but for effect, we hear it before we cut to the room. It's a sound transition from one scene to the next and it's perfectly "legal" in a spec script.

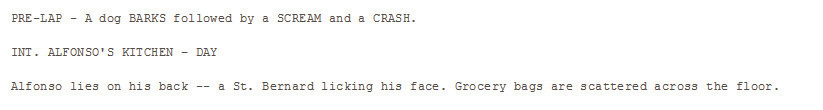

The second method is exactly the same, except you replace the V.O. with the term PRE-LAP.

If the sound is not dialogue, you can use the PRE-LAP as follows:

The second method is exactly the same, except you replace the V.O. with the term PRE-LAP.

If the sound is not dialogue, you can use the PRE-LAP as follows:

Keep Writing!

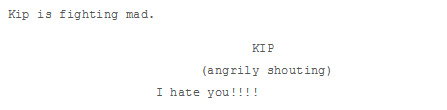

THE WRYLY FACTOR

QUESTION

At a recent conference, I heard so many contradictory "rules" about formatting that my head is spinning. Some say all of the action should be written in parentheticals [often referred to as wrylies] since producers only read the dialogue, and some say that there should be no parentheticals at all. Could you help?

ANSWER

It's true there are producers in town who only read dialogue, but that does not mean that they read the wrylies too, nor does it mean that all producers only read dialogue. Keep in mind that before a producer reads your script, a professional reader reads it from beginning to end. Finally, when a production company gets serious about a script, then several people in the company may end up reading it. So don't be unduly concerned about how much of your script will get read. You cannot control that. What you can control is what you write.

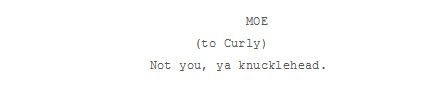

Use wrylies sparingly. If there are too many, then a reader is likely not to take them too seriously. Their main purpose is to clarify the subtext when the subtext is not already apparent. For example, if a character says "I love you" in a sarcastic way, and it is not otherwise apparent that he would be sarcastic, then that's the time to use the parenthetical (wryly). Too often, I see something like the following in a screenplay:

QUESTION

At a recent conference, I heard so many contradictory "rules" about formatting that my head is spinning. Some say all of the action should be written in parentheticals [often referred to as wrylies] since producers only read the dialogue, and some say that there should be no parentheticals at all. Could you help?

ANSWER

It's true there are producers in town who only read dialogue, but that does not mean that they read the wrylies too, nor does it mean that all producers only read dialogue. Keep in mind that before a producer reads your script, a professional reader reads it from beginning to end. Finally, when a production company gets serious about a script, then several people in the company may end up reading it. So don't be unduly concerned about how much of your script will get read. You cannot control that. What you can control is what you write.

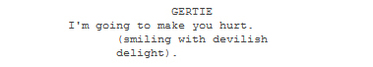

Use wrylies sparingly. If there are too many, then a reader is likely not to take them too seriously. Their main purpose is to clarify the subtext when the subtext is not already apparent. For example, if a character says "I love you" in a sarcastic way, and it is not otherwise apparent that he would be sarcastic, then that's the time to use the parenthetical (wryly). Too often, I see something like the following in a screenplay:

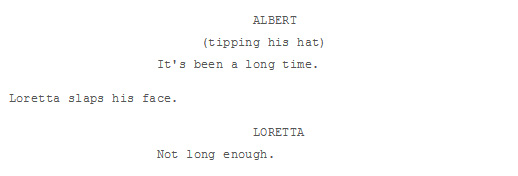

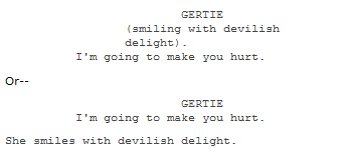

The above example says the same thing in three different ways. In this case, all that you need is the speech itself. Also, lose the exclamation points. Your speech should not look like a want ad.

Use a wryly to indicate action that can be described in a few words. I provided an example of that in the "Where to put the action" section above.

Use a wryly to indicate who the character is speaking to when that is not otherwise clear:

Use a wryly to indicate action that can be described in a few words. I provided an example of that in the "Where to put the action" section above.

Use a wryly to indicate who the character is speaking to when that is not otherwise clear:

If you follow this column, you already know that I discourage the use of the lifeless term "beat" to indicate a pause. I much prefer an adverbial, facial expression, or action that comments on either the story or the character while still implying a pause. It's an unbeatable approach.

WHERE TO PUT THE ACTION

QUESTION

I just finished an existing TV drama script and noticed something about my style for the first time. Sometimes I write a character's action on the action line [as narrative description], and sometimes I do it under the character's name itself [as a parenthetical, or actor's instruction]. Which is correct and, if they both are, can you have examples of both throughout your script, or should you just stick to one style?

ANSWER

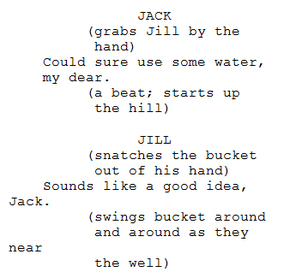

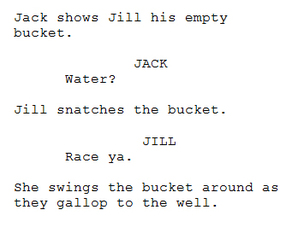

If the action only takes a few words to describe, it's okay to write it either way--as action, or as a parenthetical:

QUESTION

I just finished an existing TV drama script and noticed something about my style for the first time. Sometimes I write a character's action on the action line [as narrative description], and sometimes I do it under the character's name itself [as a parenthetical, or actor's instruction]. Which is correct and, if they both are, can you have examples of both throughout your script, or should you just stick to one style?

ANSWER

If the action only takes a few words to describe, it's okay to write it either way--as action, or as a parenthetical:

As you can see, it is okay to use both styles in your screenplay, as I did in the example above. However, any action that takes more than a few words to describe should be written as narrative description only:

Good luck and keep writing!

LOOK WHO'S PRAYING

QUESTION

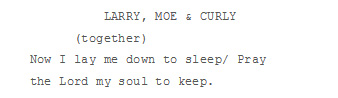

How do I write one dialogue speech for three characters to say at the same time? For example, I have a scene where three characters say the same prayer at the same time.

ANSWER

I can best answer this with an example:

QUESTION

How do I write one dialogue speech for three characters to say at the same time? For example, I have a scene where three characters say the same prayer at the same time.

ANSWER

I can best answer this with an example:

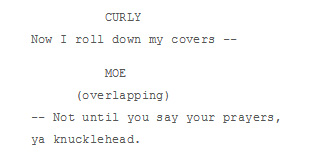

Naturally, in the above example, I could have written “at the same time" as my parenthetical, or "in unison." You may not need the parenthetical at all. Now if someone starts saying something, and the other begins before the first has finished, then that overlapping dialogue is written as follows:

POETIC LICENSE

QUESTION

How do I separate lines in a stanza of a poem?

ANSWER

Use a slash. See the example above of the Three Stooges praying in unison. And keep writing!

QUESTION

How do I separate lines in a stanza of a poem?

ANSWER

Use a slash. See the example above of the Three Stooges praying in unison. And keep writing!

PRE-LAP AND V.O.

QUESTION

I want the dialogue of a scene to begin in the previous scene. How do I do that?

ANSWER

You can use one of two methods. Here's the first.:

QUESTION

I want the dialogue of a scene to begin in the previous scene. How do I do that?

ANSWER

You can use one of two methods. Here's the first.:

The second method is to replace the V.O. in the first example with PRE-LAP or PRELAP.

Good luck and keep writing!

Good luck and keep writing!

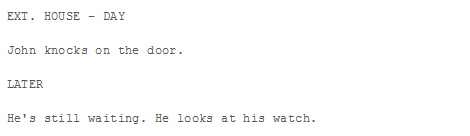

DAY, NIGHT, AND CONTINUOUS

QUESTION

There is one contest that states emphatically, "DAY and NIGHT are the only acceptable options!" But then I see you with examples such as TWILIGHT, MORNING, LATER, or even leaving it off entirely. I'd prefer to use these more descriptive examples, as I think they lend color to a script, but am a bit scared I'll tick off a contest judge or two.

ANSWER

Use DAY or NIGHT. Only use something else, such as TWILIGHT or MORNING, when there is an overriding dramatic purpose for it.LATER is a secondary scene heading that is perfectly okay to use whenever it's called for. For example:

QUESTION

There is one contest that states emphatically, "DAY and NIGHT are the only acceptable options!" But then I see you with examples such as TWILIGHT, MORNING, LATER, or even leaving it off entirely. I'd prefer to use these more descriptive examples, as I think they lend color to a script, but am a bit scared I'll tick off a contest judge or two.

ANSWER

Use DAY or NIGHT. Only use something else, such as TWILIGHT or MORNING, when there is an overriding dramatic purpose for it.LATER is a secondary scene heading that is perfectly okay to use whenever it's called for. For example:

Beyond the above response, just follow what the contest wants you to do. The same goes for producers or agents who make specific requests.Use no extension only when it's already clearly obvious that it is DAY or NIGHT. :

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

Another site even frowns on using CONTINUOUS.

ANSWER

Use CONTINUOUS when it is not otherwise obvious that the scene is CONTINUOUS. If it is already obvious, don't use it.

Good luck and keep writing!

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

Another site even frowns on using CONTINUOUS.

ANSWER

Use CONTINUOUS when it is not otherwise obvious that the scene is CONTINUOUS. If it is already obvious, don't use it.

Good luck and keep writing!

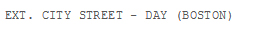

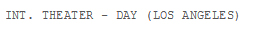

GEOGRAPHY AND PARENTHESES

QUESTION

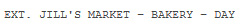

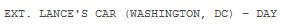

The locales for most of my script are two cities. I've designated them appropriately, such as the following:

QUESTION

The locales for most of my script are two cities. I've designated them appropriately, such as the following:

And

Is it necessary to label each scene following the initial designation as either Boston or Los Angeles with these parentheticals: (BOSTON) / (LOS ANGELES)? Or is it assumed that the following scenes are still in the designated city until it switches to the other city?

ANSWER

It’s not necessary to label every scene.

Just establish Boston and Los Angeles. You don't need to continually remind the reader. The exception is at those moments or scenes where you think the reader could get lost.

In your first example above, you have an exterior location, so you could write this:

ANSWER

It’s not necessary to label every scene.

Just establish Boston and Los Angeles. You don't need to continually remind the reader. The exception is at those moments or scenes where you think the reader could get lost.

In your first example above, you have an exterior location, so you could write this:

You don't need the parenthetical because Boston is an exterior location. Here's another way to write the same scene heading:

The second example should be written like this:

Keep the location in the location section of the scene heading.

As an alternative, you could establish the city before going to a smaller location. For example:

As an alternative, you could establish the city before going to a smaller location. For example:

The City of Angles glistens in the sun.

That’s an "establishing shot," and it’s not necessary to write ESTABLISHING as part of the scene heading.

Good luck and keep writing!

Good luck and keep writing!

A FLASHBACK WITHIN A FLASHBACK

QUESTION

I am stumped and cannot find a solution on the world wide web or anywhere else. I don't want to confuse the reader by signifying a flashback within a flashback. So my script starts with current time/space which is Act 1. During that first act, there is a flashback that takes up most of the story until the Climax. Within that flashback, at the Midpoint of Act 2, there is another flashback, which lasts 1 to 2 pages, and comes back to the more current flashback. How can I not confuse the reader?

ANSWER

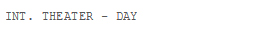

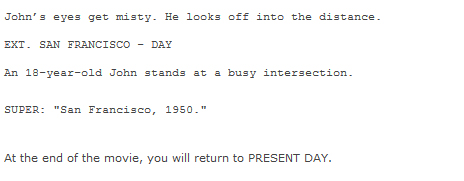

You are using the storyteller device, which was also used in "Saving Private Ryan." That's where a character or a series of scenes introduces the main story that takes place in the past. Since most of the movie takes place in the past, use a SUPER (short for "superimpose") rather than a FLASHBACK. In other words, don't call the first flashback a flashback. Thus, you will label your first flashback as follows:

QUESTION

I am stumped and cannot find a solution on the world wide web or anywhere else. I don't want to confuse the reader by signifying a flashback within a flashback. So my script starts with current time/space which is Act 1. During that first act, there is a flashback that takes up most of the story until the Climax. Within that flashback, at the Midpoint of Act 2, there is another flashback, which lasts 1 to 2 pages, and comes back to the more current flashback. How can I not confuse the reader?

ANSWER

You are using the storyteller device, which was also used in "Saving Private Ryan." That's where a character or a series of scenes introduces the main story that takes place in the past. Since most of the movie takes place in the past, use a SUPER (short for "superimpose") rather than a FLASHBACK. In other words, don't call the first flashback a flashback. Thus, you will label your first flashback as follows:

And then refer to the second flashback as a FLASHBACK. In other words, format the second FLASHBACK like you would any other FLASHBACK. No reader will get lost.

However, what if you have a FLASHBACK within a FLASHBACK where both are relatively short (that is, not using the storyteller device)? The solution is to be clear in your labeling and description. I'll illustrate with a brief example:

However, what if you have a FLASHBACK within a FLASHBACK where both are relatively short (that is, not using the storyteller device)? The solution is to be clear in your labeling and description. I'll illustrate with a brief example:

Good luck and keep writing!

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

FIVE MORE QUESTIONS

QUESTION

Please answer the following formatting questions, if you'd be so kind.

ANSWER

I'll list them below for you, first your numbered questions in Italics, followed by my answers. (Reader, how many of these do you already know the answer to?)

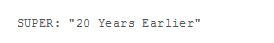

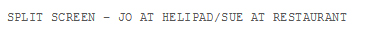

Question 1. What is the format for a split-screen.?

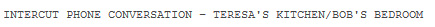

Handle it like an INTERCUT::

QUESTION

Please answer the following formatting questions, if you'd be so kind.

ANSWER

I'll list them below for you, first your numbered questions in Italics, followed by my answers. (Reader, how many of these do you already know the answer to?)

Question 1. What is the format for a split-screen.?

Handle it like an INTERCUT::

And then keep the reader oriented as to where we are as you describe the action. If this is a phone conversation, write::

And then write out the dialogue.:

Question 2. Even though crosscutting or parallel action cutting is an editing term, it should be visualized and written in the screenplay itself right?

Right; don't use the term CROSS-CUTTING. Just use master scene headings and describe what we see. Here's a quick example:

Question 2. Even though crosscutting or parallel action cutting is an editing term, it should be visualized and written in the screenplay itself right?

Right; don't use the term CROSS-CUTTING. Just use master scene headings and describe what we see. Here's a quick example:

And then keep going back and forth, or consider using the INTERCUT.

Describe what we see.

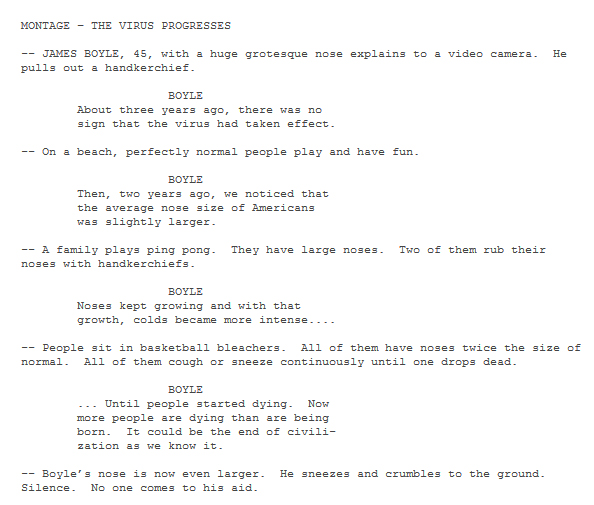

Question 3. Is it okay to format a montage where there is a voiceover along with it?

Yes, you can do that in any kind of scene whether it's a montage, dream, flashback, or what-have-you.

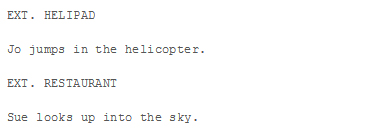

Question 4. In some movies, we see the date, time or location on screen. How do I format this in the screenplay?

Use a SUPER (for superimpose) as follows:

Describe what we see.

Question 3. Is it okay to format a montage where there is a voiceover along with it?

Yes, you can do that in any kind of scene whether it's a montage, dream, flashback, or what-have-you.

Question 4. In some movies, we see the date, time or location on screen. How do I format this in the screenplay?

Use a SUPER (for superimpose) as follows:

Question 5. Do I write OK or okay?Okay. And keep writing.

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

FIVE QUESTIONS

QUESTION

Please answer the following formatting questions, if you'd be so kind.

ANSWER

I'll list them below for you, first your numbered questions in Italics, followed by my answers. (Reader, how many of these do you already know the answer to?)

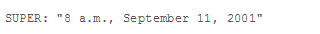

Question 1. How do I format a scene where the characters talk, but we don't hear it (muted conversation as background music is playing)? Do I just write, A and B in a heated argument etc.?

Use MOS. MOS means "without sound." So you could write something like this:

QUESTION

Please answer the following formatting questions, if you'd be so kind.

ANSWER

I'll list them below for you, first your numbered questions in Italics, followed by my answers. (Reader, how many of these do you already know the answer to?)

Question 1. How do I format a scene where the characters talk, but we don't hear it (muted conversation as background music is playing)? Do I just write, A and B in a heated argument etc.?

Use MOS. MOS means "without sound." So you could write something like this:

Question 2. a) Can I have 2 consecutive montages? b) If yes, can I have 2 consecutive montages in the same location but during different time like night and the next morning?Yes, but it seems odd that you would need two, but there's no rule against it. With your Question #b, just have one montage with a change in time. In other words, separate the first montage from the second with a secondary scene heading indicating the time change:

Question 3. How do I format a scene where the conversation is heard in very low volume like we just hear, ok, hmm etc.,? Do I just write the dialogues or should I mention that the conversation is heard feebly on screen?Just describe what we hear, and if the audience hears the words, then write them out as dialogue. For example:

Question 4. When describing action, I have seen in many scripts, 3 hyphens "---" is that correct?For a dash in narrative description or dialogue, use a space, followed by two hyphens, followed by a space -- like that. Don't use three.

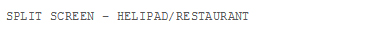

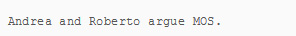

Question 5. Can I use the word "some" in scene heading like "SOME HELIPAD", "SOME RESTAURANT" where it is not absolutely essential to mention the exact town or city name?Mention the exact town or place if that's important. Otherwise, just write helipad or restaurant; for example:

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

SOUNDS ARE SOUNDS, WORDS ARE WORDS

QUESTION

In my script, I have characters who make a lot of sounds, and sometimes I have written something like the following:

QUESTION

In my script, I have characters who make a lot of sounds, and sometimes I have written something like the following:

So my question is, may I write parentheticals without any actual dialogue?

ANSWER

No. Dialogue consists of the actual words spoken by the character. Any other utterances are just sounds and should be written as narrative description, as follows:

ANSWER

No. Dialogue consists of the actual words spoken by the character. Any other utterances are just sounds and should be written as narrative description, as follows:

The same is true of the sounds made by animals. Even though they may be communicating, write their barks and meows as sounds. If the sounds are crucial, and you want to emphasize them, it's okay to place them in CAPS, but it's not necessary that you do so.

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

NOTICE: The new, 4th edition of Dr. Format Tells All is now available. Check it out at http://www.keepwriting.com/drformat/index.htm.

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS CARMEN?

QUESTION

If someone is writing a script that takes place in two separate geographical locations; e.g., Cabin on Cape Cod and Tundra of Southern Chile, what is the best way to show the reader that the scene has not just changed minor locations but entire continents? Also, with regard to the last question, this is the kind of thing I have been doing with my headings.

QUESTION

If someone is writing a script that takes place in two separate geographical locations; e.g., Cabin on Cape Cod and Tundra of Southern Chile, what is the best way to show the reader that the scene has not just changed minor locations but entire continents? Also, with regard to the last question, this is the kind of thing I have been doing with my headings.

ANSWER

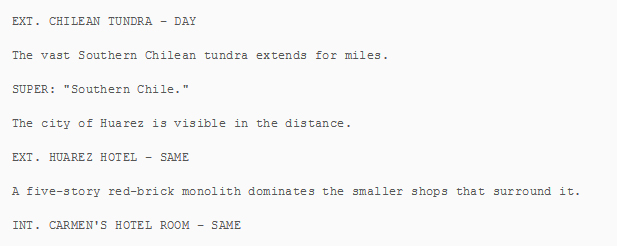

A scene heading should indicate the specific location of the scene, not everything you know about that location. Also, unless absolutely necessary, use DAY or NIGHT. Thus, I would revise your above example to the following:

A scene heading should indicate the specific location of the scene, not everything you know about that location. Also, unless absolutely necessary, use DAY or NIGHT. Thus, I would revise your above example to the following:

Carmen's hotel room is the specific location of the scene. All the other information should come out in narrative description or previous scene headings. Here's an example of what I mean:

You could replace SAME with CONTINUOUS if you wish. It's your choice.

HOW MUCH DETAIL? QUESTION

After watching movies like The Ring and Identity, I was wondering how much of the script actually turns into the visuals we see on the screen. Does the writer simply provide his/her version with dialogue and minor details and the director creates his/her own vision for the screen? My main question is when writing, how much description of key actions can the writer use throughout the script if it is relevant to the story?

ANSWER

If an action moves the story forward or adds to character, then write it. A spec script should contain specific details, but only those details that are important to the story or which reveal character.

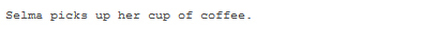

For example, here is a small detail from a script.

After watching movies like The Ring and Identity, I was wondering how much of the script actually turns into the visuals we see on the screen. Does the writer simply provide his/her version with dialogue and minor details and the director creates his/her own vision for the screen? My main question is when writing, how much description of key actions can the writer use throughout the script if it is relevant to the story?

ANSWER

If an action moves the story forward or adds to character, then write it. A spec script should contain specific details, but only those details that are important to the story or which reveal character.

For example, here is a small detail from a script.

Normally, this incidental detail is unnecessary. It's not important enough to keep. On the other hand, if there is poison in that cup of coffee, then it is a key detail that should be in the script.

If there is a fight scene, describe the scene so that the reader can visualize it. You don't have to choreograph the fight, but you need to describe blows and tumbles. What the director chooses to use or not use is up to him/her.

Remember, your job is to give the script reader goose bumps, tense up her muscles, make her laugh, or bring tears to his eyes. You can't do that with general or vague details such as "They fight," or "they make love." At the same time, don't add unnecessary details. Remember, the more you write, the more you will get a sense of how much detail to add. So keep writing.

If there is a fight scene, describe the scene so that the reader can visualize it. You don't have to choreograph the fight, but you need to describe blows and tumbles. What the director chooses to use or not use is up to him/her.

Remember, your job is to give the script reader goose bumps, tense up her muscles, make her laugh, or bring tears to his eyes. You can't do that with general or vague details such as "They fight," or "they make love." At the same time, don't add unnecessary details. Remember, the more you write, the more you will get a sense of how much detail to add. So keep writing.

TIME LAPSES QUESTION

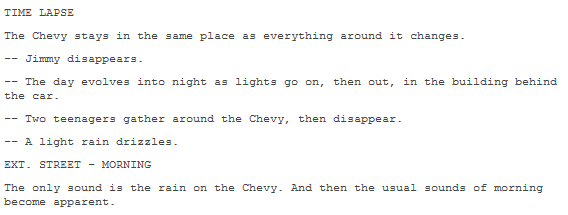

I'm stumped. I want to show a time lapse from day to night for a story reason. A character, Jimmy, parks a Chevy automobile next to a building; someone is locked in the trunk (established in an earlier scene). I want to focus on the Chevy while everything around it changes. Jimmy will stand by the car and then disappear. The sequence will end in a light rain for the next scene. How do I format that?

ANSWER

The fact that you have a "story reason" for this time lapse is what prompted me to respond. I would use a format that is similar to the MONTAGE. How about something like this?

I'm stumped. I want to show a time lapse from day to night for a story reason. A character, Jimmy, parks a Chevy automobile next to a building; someone is locked in the trunk (established in an earlier scene). I want to focus on the Chevy while everything around it changes. Jimmy will stand by the car and then disappear. The sequence will end in a light rain for the next scene. How do I format that?

ANSWER

The fact that you have a "story reason" for this time lapse is what prompted me to respond. I would use a format that is similar to the MONTAGE. How about something like this?

Keep writing.

THREE, FIVE, OR NINE ACTS? QUESTION

What are your thoughts regarding nine acts versus three acts?

ANSWER

Well, a nine-act story still has three main parts. It has a beginning middle and end, just like a three-act story. Some screenwriters like to think in terms of four acts—each about equal length. They still have a beginning (which focuses on establishing story, characters, and situation), middle (mostly concerned with complications and a rising conflict, culminating in some kind of crisis), and end (the showdown and denouement). Shakespeare used five acts, and even when he was in love, there was a beginning, middle (Acts 2, 3, and 4), and end. Most TV MOWs (movies-of-the-week) have seven acts. The first act is the beginning, and the last two are usually the end.

Basic dramatic structure is about the same for everyone. Now, how you specifically apply it to the content of your story requires some creativity and skill, and how you present the content of your story so that it is dramatic and compelling also requires some creativity and skill.

AND SITUATION COMEDY? QUESTION

...But isn't a situation comedy just two acts?

ANSWER

Yes, it has a teaser, the first act, the second act, and a tag or epilogue. However, it still has a beginning, middle, and end. The way it differs from a screenplay is that the middle is divided by a Pinch that is one of the following: 1) The funniest thing in the sitcom that makes us anticipate more hilarity while the commercial plays, 2) A very serious and dramatic turning point that makes us wonder what is going to happen next while the commercial plays, or 3) A funny twist that makes us wonder what is going to happen next while the commercial plays.

May what happens next involve a six-figure contract. Good luck and keep writing.

What are your thoughts regarding nine acts versus three acts?

ANSWER

Well, a nine-act story still has three main parts. It has a beginning middle and end, just like a three-act story. Some screenwriters like to think in terms of four acts—each about equal length. They still have a beginning (which focuses on establishing story, characters, and situation), middle (mostly concerned with complications and a rising conflict, culminating in some kind of crisis), and end (the showdown and denouement). Shakespeare used five acts, and even when he was in love, there was a beginning, middle (Acts 2, 3, and 4), and end. Most TV MOWs (movies-of-the-week) have seven acts. The first act is the beginning, and the last two are usually the end.

Basic dramatic structure is about the same for everyone. Now, how you specifically apply it to the content of your story requires some creativity and skill, and how you present the content of your story so that it is dramatic and compelling also requires some creativity and skill.

AND SITUATION COMEDY? QUESTION

...But isn't a situation comedy just two acts?

ANSWER

Yes, it has a teaser, the first act, the second act, and a tag or epilogue. However, it still has a beginning, middle, and end. The way it differs from a screenplay is that the middle is divided by a Pinch that is one of the following: 1) The funniest thing in the sitcom that makes us anticipate more hilarity while the commercial plays, 2) A very serious and dramatic turning point that makes us wonder what is going to happen next while the commercial plays, or 3) A funny twist that makes us wonder what is going to happen next while the commercial plays.

May what happens next involve a six-figure contract. Good luck and keep writing.

SOUNDING OFF QUESTION

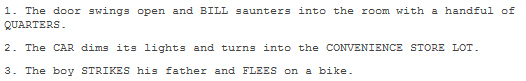

I understand that SOUNDS are sometimes written in CAPS, but I have also seen characters (after their initial introduction), places, and actions put in all-CAPS. For example:

I understand that SOUNDS are sometimes written in CAPS, but I have also seen characters (after their initial introduction), places, and actions put in all-CAPS. For example:

What is your opinion on CAPS being used in this manner? I see it all the time, yet I've never read anything about it in formatting books or the like.

ANSWER

The reason you see it a lot is because you are (likely) reading shooting scripts. The reason you seldom see it in screenwriting books is because they generally provide instruction for spec scripts. A spec script is one written to sell; a shooting script is written for the shoot. In a shooting script, sounds and props are CAPPED so that the production manager can easily break down the script (prepare a shooting schedule, make lists of props and sound effects, and so on). On occasion, you may find a shooting script where all character names are CAPPED so that they can be tracked in the breakdown.

Unfortunately, many developing writers use these shooting script conventions in their spec scripts, or they want to emphasize a word by CAPPING it. The use of all-CAPS is hard on the eyes. Let's review your three examples in view of generally accepted spec writing conventions.

1. If this is not Bill's first appearance in the screenplay, his name should not appear in CAPS. The QUARTERS are a prop and should not be CAPPED in a spec script. In fact, as a general rule, nouns are not placed in CAPS, and that includes props, objects, places, and things. (The exception is the name of a character when he or she first appears in the screenplay.) Thus, this sentence should be written as follows:

ANSWER

The reason you see it a lot is because you are (likely) reading shooting scripts. The reason you seldom see it in screenwriting books is because they generally provide instruction for spec scripts. A spec script is one written to sell; a shooting script is written for the shoot. In a shooting script, sounds and props are CAPPED so that the production manager can easily break down the script (prepare a shooting schedule, make lists of props and sound effects, and so on). On occasion, you may find a shooting script where all character names are CAPPED so that they can be tracked in the breakdown.

Unfortunately, many developing writers use these shooting script conventions in their spec scripts, or they want to emphasize a word by CAPPING it. The use of all-CAPS is hard on the eyes. Let's review your three examples in view of generally accepted spec writing conventions.

1. If this is not Bill's first appearance in the screenplay, his name should not appear in CAPS. The QUARTERS are a prop and should not be CAPPED in a spec script. In fact, as a general rule, nouns are not placed in CAPS, and that includes props, objects, places, and things. (The exception is the name of a character when he or she first appears in the screenplay.) Thus, this sentence should be written as follows:

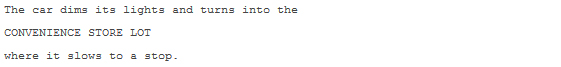

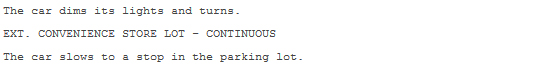

2. The word "car" should not appear in CAPS. It's a noun. The CONVENIENCE STORE LOT appears to be a new location. If so, it should be written as a scene heading (slug line). If the convenience store lot is a secondary location that is part of the master scene location, then this sentence would be written as follows:

If the convenience store lot is a new master scene location, then the sentence should be revised as follows.

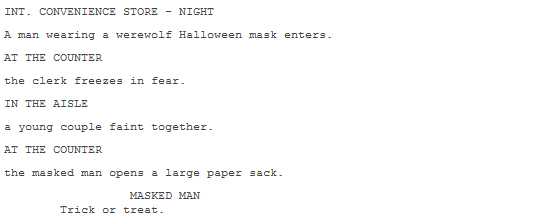

What's the difference between a master scene heading and a secondary scene heading? The master scene heading presents a master location. A secondary scene heading presents a location that is part of the master location. Here's an example.

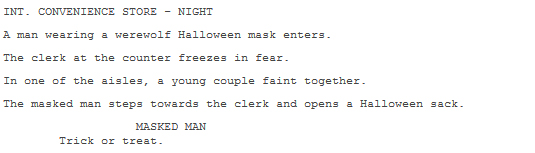

In the above example, you can clearly see that the counter and aisle are secondary locations that are part of the primary or master location (the store). Even though the above example is in correct format, the scene doesn't have to be written that way. What follows would also be correct and probably preferred.

Notice, in the above scene, that there is no word in the narrative description written in CAPS.

3. In this example, the CAPS emphasize action and imply sound effects. The words "strikes" and "flees" do not need be placed in CAPS in a spec script. Although you are no longer required to CAP sounds in a spec script, it is okay to CAP important sounds, if you wish. So you might want to CAP the word "strike." It's your choice.

3. In this example, the CAPS emphasize action and imply sound effects. The words "strikes" and "flees" do not need be placed in CAPS in a spec script. Although you are no longer required to CAP sounds in a spec script, it is okay to CAP important sounds, if you wish. So you might want to CAP the word "strike." It's your choice.

MORE CAPS QUESTION

After a character is introduced as BURLY COP, what is the correct form for the remainder of the script? For instance, I have seen it written [in narrative description] as Burly Cop, burly cop, and even burly Cop. After reading hundreds of screenplays and numerous books, I have yet to find a clear-cut answer for this.

ANSWER

Burly Cop. Good luck and keep writing.

After a character is introduced as BURLY COP, what is the correct form for the remainder of the script? For instance, I have seen it written [in narrative description] as Burly Cop, burly cop, and even burly Cop. After reading hundreds of screenplays and numerous books, I have yet to find a clear-cut answer for this.

ANSWER

Burly Cop. Good luck and keep writing.

DIALOGUE IS DIALOGUE

QUESTION

I have a scene where a character discovers a journal and reads an entry from it. Since it's not really up to me whether the character reads the entry aloud or if the actual entry is displayed on screen, how should I format this in the script?

ANSWER

Before I answer the question, let me make two points. First, don't be ambiguous in a screenplay. Write what we see and hear. Either the character reads the journal out loud or the audience reads it silently—you decide in the screenplay. Yes, the director may change what you wrote later, but at least give him or her a vision of what you see.

Second, only dialogue is dialogue. You can only write in dialogue words that are spoken, shouted, or whispered.

Now, in answer to your question, I see two ways to approach this formatting problem.

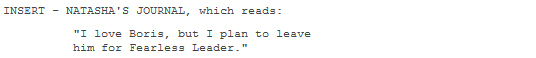

If the journal entry is very short, you might consider allowing the audience to read it. Use the INSERT for that.

QUESTION

I have a scene where a character discovers a journal and reads an entry from it. Since it's not really up to me whether the character reads the entry aloud or if the actual entry is displayed on screen, how should I format this in the script?

ANSWER

Before I answer the question, let me make two points. First, don't be ambiguous in a screenplay. Write what we see and hear. Either the character reads the journal out loud or the audience reads it silently—you decide in the screenplay. Yes, the director may change what you wrote later, but at least give him or her a vision of what you see.

Second, only dialogue is dialogue. You can only write in dialogue words that are spoken, shouted, or whispered.

Now, in answer to your question, I see two ways to approach this formatting problem.

If the journal entry is very short, you might consider allowing the audience to read it. Use the INSERT for that.

(By the way, here is how you indent using Movie Magic Screenwriter: Select the "Action" element. Then click on "Format" on the top toolbar and then "Cheat" and "Element" (F3). Select the margins you want (2.5 on the left and 2.5 on the right.)

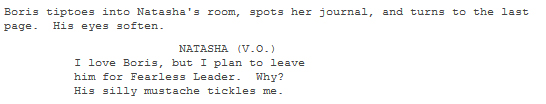

If the journal entry is longer, then perhaps your character can read it to the audience.

If the journal entry is longer, then perhaps your character can read it to the audience.

Keep writing.

PARENTHETICAL ACTION QUESTION

I have been told that I cannot end a dialogue block with an action as shown below. Is that true?

I have been told that I cannot end a dialogue block with an action as shown below. Is that true?

ANSWER

You have been told correctly. You should not end a dialogue block with an action. You can handle this situation in one of two ways.

You have been told correctly. You should not end a dialogue block with an action. You can handle this situation in one of two ways.

Or sometimes you can get away with breaking the rules.

Keep writing.

Keep writing.

I SCREAM, YOU SCREAM QUESTION

How does one write non-conversational vocal sounds, like screams? Are they written as action [narrative description]? Or are they placed under a character's name [as in the example below]?

How does one write non-conversational vocal sounds, like screams? Are they written as action [narrative description]? Or are they placed under a character's name [as in the example below]?

How about this:

ANSWER

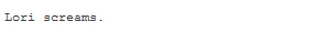

Screams, yelps, and such are sounds, and should be written as narrative description. Dialogue consists of spoken or shouted words only. The following is correct.

Screams, yelps, and such are sounds, and should be written as narrative description. Dialogue consists of spoken or shouted words only. The following is correct.

Notice that I did not write the sound (screams) in CAPS. You may CAP important sounds if you wish, but it is no longer necessary in spec writing.

Keep writing.

Keep writing.

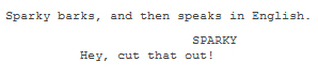

LOOK WHO’S TALKING QUESTION

What is the proper format to use for an animal that makes animal sounds, but who also talks? For example: A dog barks, then in a human voice says, "Hey, cut that out!"

ANSWER

Animal sounds should be written as narrative description. That's because only words are considered to be dialogue. Thus, you would write your example as follows.

What is the proper format to use for an animal that makes animal sounds, but who also talks? For example: A dog barks, then in a human voice says, "Hey, cut that out!"

ANSWER

Animal sounds should be written as narrative description. That's because only words are considered to be dialogue. Thus, you would write your example as follows.

Keep writing.

ABBREVIATIONS AND SLANG

QUESTION

Can you use abbreviations of words such as cos or gotta or "em in a screenplay? Or is it best to spell them out—because, got to, and them?

ANSWER

What you refer to are not abbreviations, but slang words or alternate spellings to convey pronunciation. This can be done to show a dialect or a particular accent or the particular manner of speaking that your character uses.

However, don't abbreviate in dialogue. For example, write "Doctor" rather than "Dr." Write "university" rather than "univ." Acronyms, such as C.I.A. and ASAP, are perfectly okay.

Good luck and keep writing.

QUESTION

Can you use abbreviations of words such as cos or gotta or "em in a screenplay? Or is it best to spell them out—because, got to, and them?

ANSWER

What you refer to are not abbreviations, but slang words or alternate spellings to convey pronunciation. This can be done to show a dialect or a particular accent or the particular manner of speaking that your character uses.

However, don't abbreviate in dialogue. For example, write "Doctor" rather than "Dr." Write "university" rather than "univ." Acronyms, such as C.I.A. and ASAP, are perfectly okay.

Good luck and keep writing.

WHY NOT USE CAMERA DIRECTIONS? QUESTION:

Dave, can you give me one good reason why I shouldn't include camera directions in my script? After all, I want the director to see my visual intent.

ANSWER:

I'll give you three.

1. You are not writing primarily for the director, but for the reader, and most, if not all, professional readers don't like camera directions.

2. A reader likes readability; that is, a script that is easy to read. CAPS are hard on the eyes and camera directions break up the flow of the story. A spec script should direct the camera without using camera directions; that will give the director your "visual intent."

For example, don't write something like this:

Dave, can you give me one good reason why I shouldn't include camera directions in my script? After all, I want the director to see my visual intent.

ANSWER:

I'll give you three.

1. You are not writing primarily for the director, but for the reader, and most, if not all, professional readers don't like camera directions.

2. A reader likes readability; that is, a script that is easy to read. CAPS are hard on the eyes and camera directions break up the flow of the story. A spec script should direct the camera without using camera directions; that will give the director your "visual intent."

For example, don't write something like this:

Instead, write something like this:

That has to be a CLOSE UP, and it's a lot easier to read.

3. Your scene may not be shot the way you envision it anyway. When a scene is blocked, a director often finds that adjustments have to be made.

For example, in LITTLE MISS SUNSHINE, the pier scene where Dwayne tells Frank he'll find a way to fly was originally written to be shot while the two were surfing. Thus, a wave pouring over the characters could be seen as symbolic of baptism or rebirth. In reality, it was hard to shoot and looked silly with wave after wave coming during this serious moment. And so they shot it again on the pier, and that's the version that was kept.

Good luck and keep writing.

3. Your scene may not be shot the way you envision it anyway. When a scene is blocked, a director often finds that adjustments have to be made.

For example, in LITTLE MISS SUNSHINE, the pier scene where Dwayne tells Frank he'll find a way to fly was originally written to be shot while the two were surfing. Thus, a wave pouring over the characters could be seen as symbolic of baptism or rebirth. In reality, it was hard to shoot and looked silly with wave after wave coming during this serious moment. And so they shot it again on the pier, and that's the version that was kept.

Good luck and keep writing.

ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND NUMBERS QUESTION

Would you please tell me if it is professional/acceptable to use acronyms when writing a spec script? For example, may I use MCC for Mobile Command Center?

ANSWER

Acronyms are okay. Just make sure the reader knows what they stand for. The main thing is to be absolutely clear so that the reader does not get confused. You don’t want a reader wondering what MCC stands for.

In dialogue, if you want the actor to say the individual letters of an acronym, then separate them with hyphens or periods, as follows: M.C.C. or M-C-C. Use the hyphens only if the character is spelling a word.

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

Can I abbreviate words; for example, hwy for highway?

ANSWER

In the words of William Safire, “Don’t abbrev.” Do not abbreviate regular words like highway. It comes across as sloppy writing. In dialogue speeches particularly, you must always write out the words.

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

What about numbers?

ANSWER

Numbers should be written out as words in dialogue speeches. In narrative description, use your best adjustment.

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

Would you please tell me if it is professional/acceptable to use acronyms when writing a spec script? For example, may I use MCC for Mobile Command Center?

ANSWER

Acronyms are okay. Just make sure the reader knows what they stand for. The main thing is to be absolutely clear so that the reader does not get confused. You don’t want a reader wondering what MCC stands for.

In dialogue, if you want the actor to say the individual letters of an acronym, then separate them with hyphens or periods, as follows: M.C.C. or M-C-C. Use the hyphens only if the character is spelling a word.

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

Can I abbreviate words; for example, hwy for highway?

ANSWER

In the words of William Safire, “Don’t abbrev.” Do not abbreviate regular words like highway. It comes across as sloppy writing. In dialogue speeches particularly, you must always write out the words.

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION

What about numbers?

ANSWER

Numbers should be written out as words in dialogue speeches. In narrative description, use your best adjustment.

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

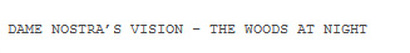

VISIONS, HALLUCINATIONS, AND MIRAGES QUESTION

Say you’re writing a scene where somebody is seeing something mentally (presumably the people with him or her wouldn’t see whatever the image was). You want the audience to see what the character is seeing as well. How would you write that?

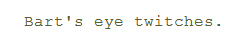

ANSWER

Let’s assume that your character’s name is Sybil. Just write what the audience and Sybil see, and label it clearly so that the reader knows that it is only Sybil’s vision. You would format it as you would a flashback or a dream:

Say you’re writing a scene where somebody is seeing something mentally (presumably the people with him or her wouldn’t see whatever the image was). You want the audience to see what the character is seeing as well. How would you write that?

ANSWER

Let’s assume that your character’s name is Sybil. Just write what the audience and Sybil see, and label it clearly so that the reader knows that it is only Sybil’s vision. You would format it as you would a flashback or a dream:

By labeling it as SYBIL’S VISION, you indicate that no character other than Sybil sees the vision. Notice that I made that absolutely clear in the last paragraph of narrative description that follows the vision. Use this same format for hallucinations and mirages. Always strive for clarity.

TWO NAMES ARE BETTER THAN ONE QUESTION

How does a writer denote in a spec screenplay the fact that a character has a double identity, and is known to individual characters under two separate identities? Example: a character is known as RALPH to one set of characters, but JIMBO to another—do you type both RALPH/JIMBO each time he speaks dialogue in the screenplay? Bear in mind that the crux of the story is that he appears as a good guy to one set of characters and as a dirty rat to another set of characters.

ANSWER

You ask a good question, since it will be important to not confuse the reader. Clarity is the overriding principle in cases like this one. That is why you should normally use the same name in your character cue throughout the screenplay. Thus, I believe the best solution is the one you suggest. Refer to the character as RALPH/JIMBO in the dialogue character cue whenever he speaks, as follows:

How does a writer denote in a spec screenplay the fact that a character has a double identity, and is known to individual characters under two separate identities? Example: a character is known as RALPH to one set of characters, but JIMBO to another—do you type both RALPH/JIMBO each time he speaks dialogue in the screenplay? Bear in mind that the crux of the story is that he appears as a good guy to one set of characters and as a dirty rat to another set of characters.

ANSWER

You ask a good question, since it will be important to not confuse the reader. Clarity is the overriding principle in cases like this one. That is why you should normally use the same name in your character cue throughout the screenplay. Thus, I believe the best solution is the one you suggest. Refer to the character as RALPH/JIMBO in the dialogue character cue whenever he speaks, as follows:

Now if this character’s true identity is RALPH and that’s established early, then consider referring to him as RALPH (in the character cue) throughout the entire screenplay, even though some or most characters call him something else. That is what happens in NORTH BY NORTHWEST. We know that Cary Grant is Roger Thornhill, even though most people call him by another name during the majority of the movie. Thus, the character cue shows THORNHILL throughout the entire script.

Finally, if the character is known as RALPH throughout the screenplay and then later in the screenplay, his actual name is revealed to be JIMBO, then type RALPH in the character cue until his true name is revealed, and refer to him as RALPH/JIMBO thereafter.

Finally, if the character is known as RALPH throughout the screenplay and then later in the screenplay, his actual name is revealed to be JIMBO, then type RALPH in the character cue until his true name is revealed, and refer to him as RALPH/JIMBO thereafter.

I'M OKAY IF YOU'RE OK QUESTION

OK or Okay? I have an editor friend of mine who keeps correcting my "OK's"! She says they need to be spelled out as "okay," but I think "OK" is acceptable. Please help.

ANSWER

Technically, your editor is correct. "Okay" is a word. "OK" is an acronym with many theories of origin. But most readers don't care which you use. Even so, everything will be okay if you use okay…and keep writing.

OK or Okay? I have an editor friend of mine who keeps correcting my "OK's"! She says they need to be spelled out as "okay," but I think "OK" is acceptable. Please help.

ANSWER

Technically, your editor is correct. "Okay" is a word. "OK" is an acronym with many theories of origin. But most readers don't care which you use. Even so, everything will be okay if you use okay…and keep writing.

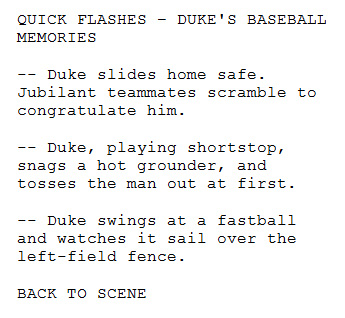

MAGICAL FLASHBACKS QUESTION

What about flashbacks that use magic? Would I have to note that it's a psychic or magical flashback? For example, a psychic detective picks up a hairbrush handle. Then we see what is in his head: a young woman brushing her hair when a man in dark apparel comes through the window.

ANSWER

This is a great question. You would handle the formatting just like a flashback, but you might use different labeling; in other words, you could choose to not call it a flashback for purposes of clarity. Here's just one possible example:

What about flashbacks that use magic? Would I have to note that it's a psychic or magical flashback? For example, a psychic detective picks up a hairbrush handle. Then we see what is in his head: a young woman brushing her hair when a man in dark apparel comes through the window.

ANSWER

This is a great question. You would handle the formatting just like a flashback, but you might use different labeling; in other words, you could choose to not call it a flashback for purposes of clarity. Here's just one possible example:

Naturally, if the woman and the man in dark apparel are appearing in the script for this first time, you would place their names or labels in all-CAPS (such as DARK MAN). And then you would keep writing!

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected]..

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected]..

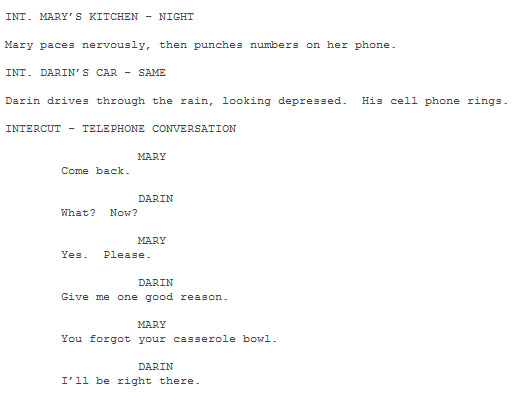

INFLAMMATORY INTERCUTS QUESTION

I once had a writing instructor say a writer should not use words that "do the director's job"—it's the sign of a novice. Might using the INTERCUT be considered telling the director how to direct?

ANSWER

The INTERCUT is mainly used for phone conversations; its purpose is to show both speaking parties, but it essentially communicates to the reader (and the eventual director): "Show whomever you want to show when you want to show him or her." So in this sense, the INTERCUT actually gives license to the director. In addition, if you choose to use the INTERCUT for a dramatic reason, then the reader will see that purpose. For example, it may be more suspenseful in one scene to only show one character in a phone conversation so that we (the audience) can't see who is calling her or hear what is said. In another scene, it might make more dramatic sense to let us (the audience) hear what the other character says without showing him. When you make writing decisions based on story and character issues, then you're much less likely to offend the reader and the eventual director. What is irritating to readers is a screenplay jammed with camera directions, shot descriptions, and editing directions without a compelling dramatic or comedic objective. Even then, it's wise to avoid those technical intrusions. The INTERCUT is seldom seen as a technical intrusion.

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

I once had a writing instructor say a writer should not use words that "do the director's job"—it's the sign of a novice. Might using the INTERCUT be considered telling the director how to direct?

ANSWER

The INTERCUT is mainly used for phone conversations; its purpose is to show both speaking parties, but it essentially communicates to the reader (and the eventual director): "Show whomever you want to show when you want to show him or her." So in this sense, the INTERCUT actually gives license to the director. In addition, if you choose to use the INTERCUT for a dramatic reason, then the reader will see that purpose. For example, it may be more suspenseful in one scene to only show one character in a phone conversation so that we (the audience) can't see who is calling her or hear what is said. In another scene, it might make more dramatic sense to let us (the audience) hear what the other character says without showing him. When you make writing decisions based on story and character issues, then you're much less likely to offend the reader and the eventual director. What is irritating to readers is a screenplay jammed with camera directions, shot descriptions, and editing directions without a compelling dramatic or comedic objective. Even then, it's wise to avoid those technical intrusions. The INTERCUT is seldom seen as a technical intrusion.

Keep writing and take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

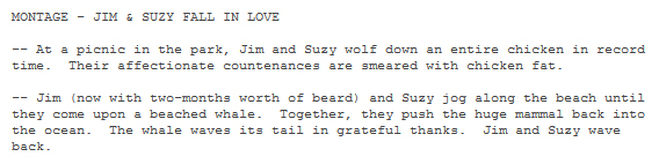

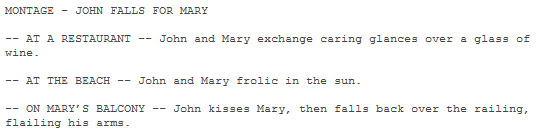

THE FALLING IN LOVE MONTAGE QUESTION

I'm at the point in my romantic comedy script where the two characters get together and fall in love. I want to show the audience that two months go by in the characters' lives and in the things they do; that is, go on a picnic, go to the beach, attend parties, etc. Usually, in actual movies, there is music during this section. How do I write it down so that the producer/director knows what sort of sequence I am after?

ANSWER

You are referring to the montage. Use the specific shots of your montage to show "passage of time" or "falling in love" (or any other concept). Here's an example:

I'm at the point in my romantic comedy script where the two characters get together and fall in love. I want to show the audience that two months go by in the characters' lives and in the things they do; that is, go on a picnic, go to the beach, attend parties, etc. Usually, in actual movies, there is music during this section. How do I write it down so that the producer/director knows what sort of sequence I am after?

ANSWER

You are referring to the montage. Use the specific shots of your montage to show "passage of time" or "falling in love" (or any other concept). Here's an example:

And so on. You did say this was a comedy, right? :-)

In terms of passage of time, I used a beard in the above example, but you will not need to be so obvious. Normally, show passage of time by how the relationship grows or deteriorates. A classic example is the breakfast montage in Citizen Kane. Obviously, time is passing. In both A Man for All Seasons and A Beautiful Mind, there is a short montage of the seasons changing.

Incidentally, you will not indicate music in your montage. That's not your job. But certainly the filmmakers will see an opportunity to insert a hit song. Your job is to keep writing.

In terms of passage of time, I used a beard in the above example, but you will not need to be so obvious. Normally, show passage of time by how the relationship grows or deteriorates. A classic example is the breakfast montage in Citizen Kane. Obviously, time is passing. In both A Man for All Seasons and A Beautiful Mind, there is a short montage of the seasons changing.

Incidentally, you will not indicate music in your montage. That's not your job. But certainly the filmmakers will see an opportunity to insert a hit song. Your job is to keep writing.

BOLD AND COURAGEOUS HEADINGS QUESTION

What do you think of the new bold-and-underline format for scene headings?

ANSWER

I think it's perfectly okay, but completely unnecessary. The standard is still ordinary, unadorned scene headings. You'll know when that changes when the two major software companies (Final Draft and Movie Magic Screenwriter) incorporate the bold-and-underline style (or bold style, or underline style) into their applications.

In the meantime, I suggest you stick with the regular scene heading style unless a different style is specifically requested, or you have fallen in love with it and feel courageous. The main thing is to courageously keep writing!

Take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

What do you think of the new bold-and-underline format for scene headings?

ANSWER

I think it's perfectly okay, but completely unnecessary. The standard is still ordinary, unadorned scene headings. You'll know when that changes when the two major software companies (Final Draft and Movie Magic Screenwriter) incorporate the bold-and-underline style (or bold style, or underline style) into their applications.

In the meantime, I suggest you stick with the regular scene heading style unless a different style is specifically requested, or you have fallen in love with it and feel courageous. The main thing is to courageously keep writing!

Take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

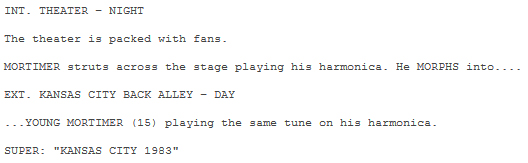

MORPHING MORTIMER QUESTION

In a number of transitions in my screenplay, we are going to see a person in the middle of an action morph into a younger version of himself without a break in the action, but indeed a change of scenery and time. How do I handle that?

ANSWER

There are many possibilities. Here is one:

In a number of transitions in my screenplay, we are going to see a person in the middle of an action morph into a younger version of himself without a break in the action, but indeed a change of scenery and time. How do I handle that?

ANSWER

There are many possibilities. Here is one:

Take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

Keep writing.

Keep writing.

DO I HAVE TO USE FORMATTING? QUESTION

Shouldn't the script writer just write a good script and let the tech people figure out all that [formatting] stuff? Does a screenwriter really need to know how to direct the camera? My experience in writing plays is that the director ignores almost all the directions; I'm pretty sure the same applies to film scripts. In other words, the scriptwriter, like the playwright, supplies the words that people speak to each other, and it is left to other professionals to film it.

ANSWER

My friend, let's take this one idea at a time.

Yes, the script writer should "write a good script," and that "good script" by definition would include correct format. It's not a script unless it's written in script format. Your premise almost sounds like this: "I'd like to write in Spanish without having to use the Spanish language." Use the language of film.

You mention the "tech people." You are not writing for the tech people, the director, or the actors. You are writing primarily for the reader (story analyst), who is almost always the first person to read a script and write a coverage for the producer or agent the script was intended for. If the coverage is negative, the agent or producer is unlikely to read the script. Readers read quickly because they have so much to read, so they expect a script to meet some minimum requirements, such as appearance (that is, correct format).

Does a screenwriter really need to know how to direct the camera? No. A spec script (written on speculation that you will sell it later) should not contain camera directions, shot descriptions, editing directions, or other technical directions normally found in a shooting script. That should come as good news. However, it helps to understand the visual aspects of film and write the script in such a way that you direct the camera without using camera directions. For example:

Shouldn't the script writer just write a good script and let the tech people figure out all that [formatting] stuff? Does a screenwriter really need to know how to direct the camera? My experience in writing plays is that the director ignores almost all the directions; I'm pretty sure the same applies to film scripts. In other words, the scriptwriter, like the playwright, supplies the words that people speak to each other, and it is left to other professionals to film it.

ANSWER

My friend, let's take this one idea at a time.

Yes, the script writer should "write a good script," and that "good script" by definition would include correct format. It's not a script unless it's written in script format. Your premise almost sounds like this: "I'd like to write in Spanish without having to use the Spanish language." Use the language of film.

You mention the "tech people." You are not writing for the tech people, the director, or the actors. You are writing primarily for the reader (story analyst), who is almost always the first person to read a script and write a coverage for the producer or agent the script was intended for. If the coverage is negative, the agent or producer is unlikely to read the script. Readers read quickly because they have so much to read, so they expect a script to meet some minimum requirements, such as appearance (that is, correct format).

Does a screenwriter really need to know how to direct the camera? No. A spec script (written on speculation that you will sell it later) should not contain camera directions, shot descriptions, editing directions, or other technical directions normally found in a shooting script. That should come as good news. However, it helps to understand the visual aspects of film and write the script in such a way that you direct the camera without using camera directions. For example:

The first paragraph implies an aerial shot or crane shot with the camera descending down to the jungle floor. The second paragraph is a CLOSE UP. A professional reader will get that.

You mention the director. The director is the second creator of the film (with the editor being the third), and certainly the director will have his or her ideas as you correctly implied. However, your script should include enough detail that your vision is not only understood by the reader, but your story involves him or her emotionally so that your script eventually becomes a movie.

Good luck with that prospect and keep writing! And take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

You mention the director. The director is the second creator of the film (with the editor being the third), and certainly the director will have his or her ideas as you correctly implied. However, your script should include enough detail that your vision is not only understood by the reader, but your story involves him or her emotionally so that your script eventually becomes a movie.

Good luck with that prospect and keep writing! And take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

TIME JUMPS MONTAGE QUESTION

My opening scene shows a small child being tended to by his mother and three other women. This scene takes place in the past, and we soon meet all of these characters again 25 years later. How do I describe everyone in my opening scene in comparison to how they will be described a few scenes later when they are older? Is it a YOUNG VINCENT? And do I describe them again later?

ANSWER

Yes and yes. Call him YOUNG VINCENT, four years old, or whatever his age is. And then when you cut to 25 years later, call him VINCENT, now 29. And then describe him just as you would if this were the first scene in the movie.

My opening scene shows a small child being tended to by his mother and three other women. This scene takes place in the past, and we soon meet all of these characters again 25 years later. How do I describe everyone in my opening scene in comparison to how they will be described a few scenes later when they are older? Is it a YOUNG VINCENT? And do I describe them again later?

ANSWER

Yes and yes. Call him YOUNG VINCENT, four years old, or whatever his age is. And then when you cut to 25 years later, call him VINCENT, now 29. And then describe him just as you would if this were the first scene in the movie.

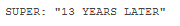

TIME STANDS STILL QUESTION

In my scene, a young newlywed couple is at a park among guests, cutting the cake. The next scene shows the same couple 13 years later, watching the tape of their wedding at the park (the previous scene). What would be the correct way to write this?

ANSWER

There are many correct ways. Let’s look at just one. I think the key to the transition will be to cut from one action to that same action on the video tape:

In my scene, a young newlywed couple is at a park among guests, cutting the cake. The next scene shows the same couple 13 years later, watching the tape of their wedding at the park (the previous scene). What would be the correct way to write this?

ANSWER

There are many correct ways. Let’s look at just one. I think the key to the transition will be to cut from one action to that same action on the video tape:

If you want to be clearer about the jump in time, you could omit that last sentence, double space, and write:

Good luck and keep writing!

CAPPING NAMES QUESTION

Should I place a name in all-CAPS for characters with no speaking parts, but which interact with other characters? In my case, I have a dog and baby who move the story forward but don’t talk.

ANSWER

When any individual character first appears in narrative description, that character’s name or label should be placed in all-CAPS that first time, even if the character doesn’t talk later. If your dog is called MAX, that name should appear in all-CAPS that first time only. The same is true of characters without names who are labeled, such as CHUBBY COP, CRYING BABY and SEXY WAITRESS.

It is not necessary to CAP groups of characters, like “the crowd,” but it’s perfectly okay to do so if you wish.

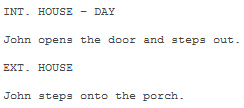

CONTINUOUS QUESTION

Someone told me that using CONTINUOUS in slug lines [scene headings] is wrong. Is that true?

ANSWER

What that person may have meant is if it is already obvious that one scene follows continuously a previous scene without any jump in time, then writing CONTINUOUS is not necessary. For example:

Should I place a name in all-CAPS for characters with no speaking parts, but which interact with other characters? In my case, I have a dog and baby who move the story forward but don’t talk.

ANSWER

When any individual character first appears in narrative description, that character’s name or label should be placed in all-CAPS that first time, even if the character doesn’t talk later. If your dog is called MAX, that name should appear in all-CAPS that first time only. The same is true of characters without names who are labeled, such as CHUBBY COP, CRYING BABY and SEXY WAITRESS.

It is not necessary to CAP groups of characters, like “the crowd,” but it’s perfectly okay to do so if you wish.

CONTINUOUS QUESTION

Someone told me that using CONTINUOUS in slug lines [scene headings] is wrong. Is that true?

ANSWER

What that person may have meant is if it is already obvious that one scene follows continuously a previous scene without any jump in time, then writing CONTINUOUS is not necessary. For example:

In the above situation, it is obvious that one scene follows the previous scene continuously. However, if that is not clear, then definitely use CONTINUOUS so that the reader doesn’t misunderstand.

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION QUESTION

How about DAY or NIGHT?

ANSWER

The same logic applies, but don’t outsmart yourself and confuse a reader who may wonder for a given scene, is it day or night?

WE THE PEOPLE QUESTION

I’d like your opinion on using “AND WE” when transitioning between scenes. I have seen this technique used in many shooting scripts.

ANSWER

Don’t use it in a spec script. As a general guideline, avoid the use of first person: AND WE, WE SEE, WE HEAR, WE MOVE, and so on. Naturally, there can be exceptions.

Good luck and keep writing! And take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION QUESTION

How about DAY or NIGHT?

ANSWER

The same logic applies, but don’t outsmart yourself and confuse a reader who may wonder for a given scene, is it day or night?

WE THE PEOPLE QUESTION

I’d like your opinion on using “AND WE” when transitioning between scenes. I have seen this technique used in many shooting scripts.

ANSWER

Don’t use it in a spec script. As a general guideline, avoid the use of first person: AND WE, WE SEE, WE HEAR, WE MOVE, and so on. Naturally, there can be exceptions.

Good luck and keep writing! And take $20 off a script evaluation by Yours Truly. Just email me for details at [email protected].

A PROFESSIONAL LOOKING SCRIPT QUESTION

How unprofessional can I be in formatting? Do I have to have everything exactly right?

ANSWER

If your story is wonderful, then the reader may overlook little formatting problems. Then again, the reader may never read your script if he or she is turned off by those “little formatting problems” when he or she glances through your script. Obviously, the story is the most important thing, but formatting is also important. In marketing, we call this packaging. Packaging is important in selling the product—your script.

Here’s the bottom line. If the formatting errors in your script are minimal, you will probably be okay. Keep in mind that different people in the biz have different ideas of what correct formatting is. Thus, be smart and follow the rules of spec formatting as best you can, and then don’t be unduly concerned. Relax and write.

How unprofessional can I be in formatting? Do I have to have everything exactly right?

ANSWER

If your story is wonderful, then the reader may overlook little formatting problems. Then again, the reader may never read your script if he or she is turned off by those “little formatting problems” when he or she glances through your script. Obviously, the story is the most important thing, but formatting is also important. In marketing, we call this packaging. Packaging is important in selling the product—your script.

Here’s the bottom line. If the formatting errors in your script are minimal, you will probably be okay. Keep in mind that different people in the biz have different ideas of what correct formatting is. Thus, be smart and follow the rules of spec formatting as best you can, and then don’t be unduly concerned. Relax and write.

THREE, FIVE, OR NINE ACTS? QUESTION

What are your thoughts regarding nine acts versus three acts?

ANSWER