Dramatica Writing Articles by James Hull

Writers Who Write the Same Main Character

July 2016

Artists tend to tread the same narrative ground. They feel drawn to themes and issues that resonate with their own personal issues and use storytelling to work through those problems. Director Christopher Nolan is no different.

Appraising Nolan's catalog of films through the eyes of Dramatica reveals a common set of elements. Memories, Understanding, Conceptualizing, and the Past all play significant parts in many of his films. In Memento, Leonard (Guy Pearce) struggles to fight against his disability with short-term memory. Inception explores the conflict involved in getting Robert (Cillian Murphy) to understand a key bit of information. And in The Prestige two magicians (Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale) scheme against each other in an effort to be the first to conceptualize the other's next move. Common areas of thematic intent wrapped up in different storytelling.

It should seem obvious then where Nolan's 2006 film Batman Begins would fall. But it wasn't.

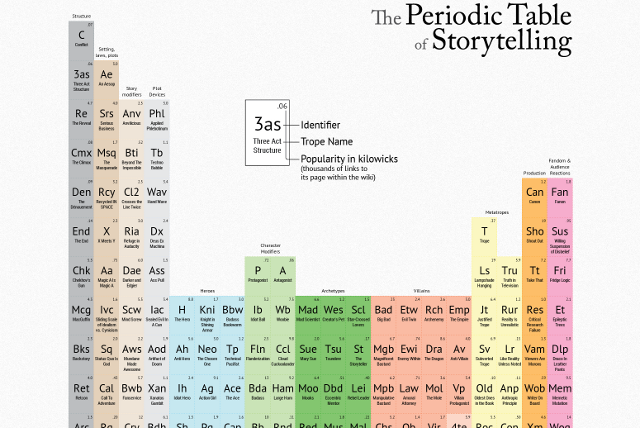

For years, I have searched for the correct storyform for this film. For those unfamiliar with the Dramatica theory of story, a storyform is a collection of seventy-five story points that maintain the message of a narrative. Dramatica's story points are not independent, but rather interdependent. They work together to provide a holistic hologram of Author's Intent and help identify why a story unfolds the way it does.

While looking for the storyform for Batman Begins, I knew that elements of Equity and Inequity would somehow be involved. Justice and restoring balance play a heavy hand in this film. And I felt certain that Issues of Interdiction would come into play–once you see someone or something headed down a dark path you often want to intercede on their behalf and fix it. But I wasn't sure where the actual Throughlines fell within the Dramatica Table of Story Elements.

Dramatica was the first theory of story to identify four distinct, yet interwoven, Throughlines within a complete narrative:

These are not separate storylines. The Main Character exists within the Overall Story. So does the Influence Character. But their subjective points-of-view rest within their individual Throughlines. This is key because these Throughlines are actually points-of-views on conflict themselves:

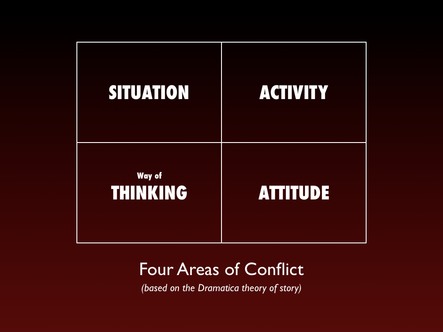

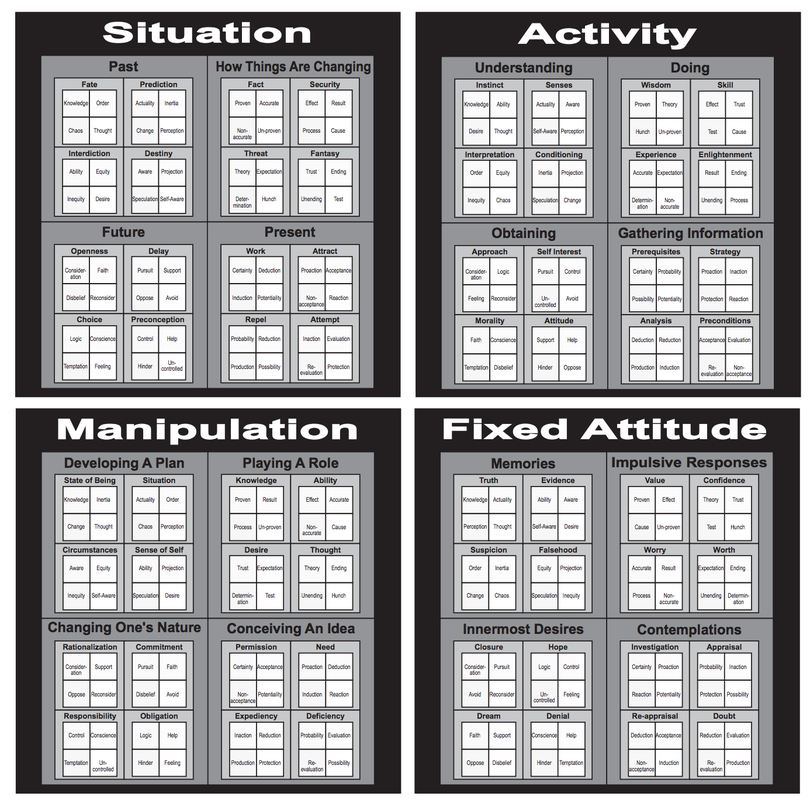

In addition to seeing Throughlines as these distinct points-of-view, Dramatica identifies four areas where conflict is found:

Four points-of-view. Four ways of seeing conflict. Attach each of the Throughlines to one of these areas of conflict and you have a complete story. Only one rule: the Overall Story Throughline and Relationship Story Throughline must be diagonally across from each other, and so must the Main Character Throughline and the Influence Character Throughline.

July 2016

Artists tend to tread the same narrative ground. They feel drawn to themes and issues that resonate with their own personal issues and use storytelling to work through those problems. Director Christopher Nolan is no different.

Appraising Nolan's catalog of films through the eyes of Dramatica reveals a common set of elements. Memories, Understanding, Conceptualizing, and the Past all play significant parts in many of his films. In Memento, Leonard (Guy Pearce) struggles to fight against his disability with short-term memory. Inception explores the conflict involved in getting Robert (Cillian Murphy) to understand a key bit of information. And in The Prestige two magicians (Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale) scheme against each other in an effort to be the first to conceptualize the other's next move. Common areas of thematic intent wrapped up in different storytelling.

It should seem obvious then where Nolan's 2006 film Batman Begins would fall. But it wasn't.

For years, I have searched for the correct storyform for this film. For those unfamiliar with the Dramatica theory of story, a storyform is a collection of seventy-five story points that maintain the message of a narrative. Dramatica's story points are not independent, but rather interdependent. They work together to provide a holistic hologram of Author's Intent and help identify why a story unfolds the way it does.

While looking for the storyform for Batman Begins, I knew that elements of Equity and Inequity would somehow be involved. Justice and restoring balance play a heavy hand in this film. And I felt certain that Issues of Interdiction would come into play–once you see someone or something headed down a dark path you often want to intercede on their behalf and fix it. But I wasn't sure where the actual Throughlines fell within the Dramatica Table of Story Elements.

Dramatica was the first theory of story to identify four distinct, yet interwoven, Throughlines within a complete narrative:

- The Overall Story Throughline (OS) -- the conflict involving everyone

- The Main Character Throughline (MC) -- the conflict personal to the central character

- The Influence Character Throughline (IC) -- the conflict provided by an alternative approach

- The Relationship Story Throughline (RS) -- the conflict that exists between the Main and Influence Character

These are not separate storylines. The Main Character exists within the Overall Story. So does the Influence Character. But their subjective points-of-view rest within their individual Throughlines. This is key because these Throughlines are actually points-of-views on conflict themselves:

- OS Throughline is THEY

- MC Throughline is I

- IC Throughline is YOU

- RS Throughline is WE

In addition to seeing Throughlines as these distinct points-of-view, Dramatica identifies four areas where conflict is found:

- fixed, external problem or Situation

- a shifting, external problem or Activity

- fixed, internal problem or Fixed Attitude

- a shifting, internal problem or Way of Thinking

Four points-of-view. Four ways of seeing conflict. Attach each of the Throughlines to one of these areas of conflict and you have a complete story. Only one rule: the Overall Story Throughline and Relationship Story Throughline must be diagonally across from each other, and so must the Main Character Throughline and the Influence Character Throughline.

So if you have an Overall Story Throughline in Activity, that means the Relationship Story Throughline will be in a Way of Thinking, or Manipulation. Think of Star Wars or Casablanca. In those films, everyone is dealing with physical conflict that needs to be stopped, while intimately a relationship explores conflict born out of manipulation.

This works for the Main Character and Influence Character dynamic as well. If you put the Main Character Throughline in Situation, that means the Influence Character Throughline will be in Fixed Attitude. Think Inside Out or Rain Man. In those films, the central character deals intimately with problems arising from status, while they face another character stuck with a certain fixation in his or her mind.

When I first saw Batman Begins in 2006, I felt for certain the Overall Story Throughline would fall under Situation. After all, there was a lot of discussion over Gotham and how it compared to civilizations in the past, and how it needed to be thrown into darkness in order for the light to rise again. Everyone found themselves dealing with that conflict.

But that would mean Bruce Wayne would have to fall into either an Activity or a Way of Thinking. Way of Thinking felt totally wrong: Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins is nothing like Hamlet or Salieri In Amadeus. Activity sounded better, but if Bruce suddenly stopped moonlighting as a vigilante he would still be personally conflicted. That's not how a Throughline works.

After ten years of struggling with identifying this film, it was time to cheat.

A Hidden Clue to the Structure

In Dramatica there is a story point known as the Main Character Approach that classifies the central character of a story into two different camps: a Do-er or a Be-er. Classifying the Main Character as one or the other defines whether the Main Character prefers to solve their personal problems externally or internally.

It also defines where the Throughline will fall.

If the Main Character prefers to solve problems externally, then their Throughline will be either in a Situation or an Activity. Once we identify where we think a problem is, we see a solution there as well. If we have an external problem we are dealing with, then we will first try to solve it externally–thus, Do-er.

If we have an internal problem we are dealing with, then we will first try to solve it internally either through a Fixed Attitude or Way of Thinking. This is why a Be-er prefers to solve their problems internally.

Note that this is only a preference. Clearly Main Characters can do both. What the Main Character Growth is trying to communicate is which one the Main Character prefers to do first. Some like to change the world around him, while other prefer to change themselves first.

Bruce Wayne is the latter.

At first, this may seem counterintuitive. Certainly Bruce spends the bulk of the film doing things. When we first meet him he takes on seven prisoners by himself, for "practice”. He engages in ninja school and spends pretty much the entire second half of the film fighting his way to victory.

But when you look at the personal moments with Wayne, those moments that are intimate to his character and his character only–you can begin to see a preference for a different kind of approach.

Personal Issues Unique to the Main Character

When looking to identify the Main Character Throughline of a story, it is important to look for those things that are unique to the Main Character and no one else. The stuff of this Throughline is the kind of stuff the Main Character would take with them into any story–not just the one in front of us. Look for their emotional baggage, those issues they are trying to overcome.

Wayne's greatest personal issue that is unique to him surrounds the murder of his parents and this idea that his fears were somehow responsible for their death. This isn't a Situation. Or an Activity. Or even a Way of Thinking. This is a Fixed Attitude.

And it shouldn't be surprising because Christopher Nolan likes Main Characters who struggle with what they think–Main Characters who struggle with their Fixed Attitudes. Leonard in Momento. Robert Angiers (Hugh Jackman) in The Prestige. Obsession with a thought drives the characters in many of Nolan's stories–including Batman Begins.

When Throughlines Fall into Place

Identifying Bruce Wayne as a Be-er dealing with a Fixed Attitude ends up forcing his Influence Character into Situation. The question is, who is Bruce Wayne's Influence Character? What relationships represents the heart of the story?

His relationship with Rachel Dawes (Katie Holmes) seems to be the likely candidate. But remember, the Influence Character is a point-of-view not a character. Rachel doesn't really challenge Bruce on his approach to things. And when she does, she is really just standing in for another character. So who stirs up all kinds of trouble because of a point-of-view they have in regards to a certain Situation?

Ra's al Ghul.

That perspective that Gotham should perish and go the way of Rome or Constantinople isn't the source of conflict everyone experiences. Rather, it is the point of view of the League of Shadows as expressed through Ra's al Ghul/Ducard (Liam Neeson).

This idea that Bruce should embrace his fears–"you fear your own power, you fear your anger, the drive to do great and terrible things”–comes from Ducard. And it is exactly what Bruce needs to hear in order to grow through his own Fixed Attitude. Ducard connects with Bruce because it is a similar, yet slightly different perspective. Similar in that it is fixed, different in that it is external whereas Bruce's perspective is internal.

This is why they can have their "You and I” moment after training. They are both alike in that they are both seeing conflict from a fixed point-of-view, but they are different in that one is external and the other internal. This dissonance fuels their interactions. That argument over the will to act is the text of Relationship Story Throughline.

Finding the Storyform for a Story

The quad of four elements below represents Ra's al Ghul's point-of-view as seen through the eyes of Dramatica. Ra's is driven by people's fears, angers, and their refusal to accept the drive deep within them to do terrible things. And this drive within himself causes him to see a lack of justice or peace as the problem in the world. And in response, he upsets the balance of things: "When a forest grows too wild, a purging fire is inevitable and natural.";

This works for the Main Character and Influence Character dynamic as well. If you put the Main Character Throughline in Situation, that means the Influence Character Throughline will be in Fixed Attitude. Think Inside Out or Rain Man. In those films, the central character deals intimately with problems arising from status, while they face another character stuck with a certain fixation in his or her mind.

When I first saw Batman Begins in 2006, I felt for certain the Overall Story Throughline would fall under Situation. After all, there was a lot of discussion over Gotham and how it compared to civilizations in the past, and how it needed to be thrown into darkness in order for the light to rise again. Everyone found themselves dealing with that conflict.

But that would mean Bruce Wayne would have to fall into either an Activity or a Way of Thinking. Way of Thinking felt totally wrong: Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins is nothing like Hamlet or Salieri In Amadeus. Activity sounded better, but if Bruce suddenly stopped moonlighting as a vigilante he would still be personally conflicted. That's not how a Throughline works.

After ten years of struggling with identifying this film, it was time to cheat.

A Hidden Clue to the Structure

In Dramatica there is a story point known as the Main Character Approach that classifies the central character of a story into two different camps: a Do-er or a Be-er. Classifying the Main Character as one or the other defines whether the Main Character prefers to solve their personal problems externally or internally.

It also defines where the Throughline will fall.

If the Main Character prefers to solve problems externally, then their Throughline will be either in a Situation or an Activity. Once we identify where we think a problem is, we see a solution there as well. If we have an external problem we are dealing with, then we will first try to solve it externally–thus, Do-er.

If we have an internal problem we are dealing with, then we will first try to solve it internally either through a Fixed Attitude or Way of Thinking. This is why a Be-er prefers to solve their problems internally.

Note that this is only a preference. Clearly Main Characters can do both. What the Main Character Growth is trying to communicate is which one the Main Character prefers to do first. Some like to change the world around him, while other prefer to change themselves first.

Bruce Wayne is the latter.

At first, this may seem counterintuitive. Certainly Bruce spends the bulk of the film doing things. When we first meet him he takes on seven prisoners by himself, for "practice”. He engages in ninja school and spends pretty much the entire second half of the film fighting his way to victory.

But when you look at the personal moments with Wayne, those moments that are intimate to his character and his character only–you can begin to see a preference for a different kind of approach.

Personal Issues Unique to the Main Character

When looking to identify the Main Character Throughline of a story, it is important to look for those things that are unique to the Main Character and no one else. The stuff of this Throughline is the kind of stuff the Main Character would take with them into any story–not just the one in front of us. Look for their emotional baggage, those issues they are trying to overcome.

Wayne's greatest personal issue that is unique to him surrounds the murder of his parents and this idea that his fears were somehow responsible for their death. This isn't a Situation. Or an Activity. Or even a Way of Thinking. This is a Fixed Attitude.

And it shouldn't be surprising because Christopher Nolan likes Main Characters who struggle with what they think–Main Characters who struggle with their Fixed Attitudes. Leonard in Momento. Robert Angiers (Hugh Jackman) in The Prestige. Obsession with a thought drives the characters in many of Nolan's stories–including Batman Begins.

When Throughlines Fall into Place

Identifying Bruce Wayne as a Be-er dealing with a Fixed Attitude ends up forcing his Influence Character into Situation. The question is, who is Bruce Wayne's Influence Character? What relationships represents the heart of the story?

His relationship with Rachel Dawes (Katie Holmes) seems to be the likely candidate. But remember, the Influence Character is a point-of-view not a character. Rachel doesn't really challenge Bruce on his approach to things. And when she does, she is really just standing in for another character. So who stirs up all kinds of trouble because of a point-of-view they have in regards to a certain Situation?

Ra's al Ghul.

That perspective that Gotham should perish and go the way of Rome or Constantinople isn't the source of conflict everyone experiences. Rather, it is the point of view of the League of Shadows as expressed through Ra's al Ghul/Ducard (Liam Neeson).

This idea that Bruce should embrace his fears–"you fear your own power, you fear your anger, the drive to do great and terrible things”–comes from Ducard. And it is exactly what Bruce needs to hear in order to grow through his own Fixed Attitude. Ducard connects with Bruce because it is a similar, yet slightly different perspective. Similar in that it is fixed, different in that it is external whereas Bruce's perspective is internal.

This is why they can have their "You and I” moment after training. They are both alike in that they are both seeing conflict from a fixed point-of-view, but they are different in that one is external and the other internal. This dissonance fuels their interactions. That argument over the will to act is the text of Relationship Story Throughline.

Finding the Storyform for a Story

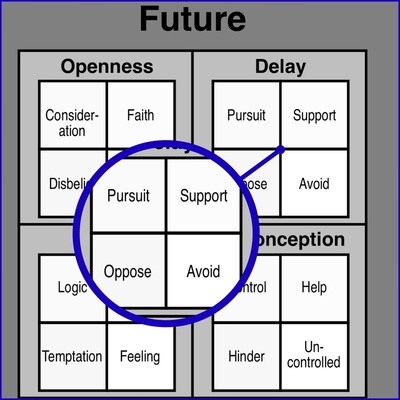

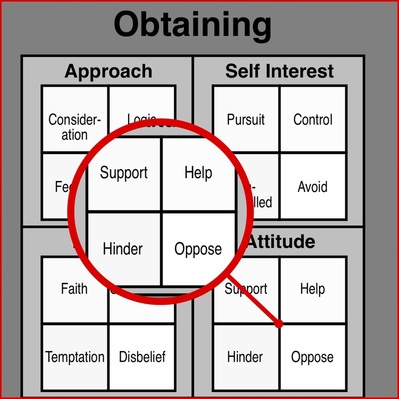

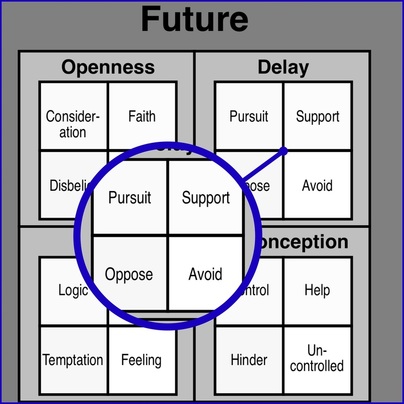

The quad of four elements below represents Ra's al Ghul's point-of-view as seen through the eyes of Dramatica. Ra's is driven by people's fears, angers, and their refusal to accept the drive deep within them to do terrible things. And this drive within himself causes him to see a lack of justice or peace as the problem in the world. And in response, he upsets the balance of things: "When a forest grows too wild, a purging fire is inevitable and natural.";

The Influence Character Quad of Batman Begins The Influence Character Quad of Batman Begins

From there, Dramatica begins to work its magic and predicts story elements not selected. For Ra's Issue of Interdiction to work, Bruce himself must be facing an Issue of Suspicion. The suspicion that he had something to do with the murder of his family, and the suspicion that he is somewhat like his father–who also failed to act.

For Ra's Concern of the Past to work (which is forced by our selection of the Issue of Interdiction) then Bruce's Concern must have something to do with Memories. Anytime he steps out of his role as billionaire vigilante and confronts his own demons, they always have something to do with suppressed Memories.

The magic of Dramatica is simply balance. If an Influence Character looks to the Past, then a Main Character must look to their Memories. If an Influence Character looks to Intercede, then a Main Character must look to their own Suspicions. Whether Christopher Nolan or screenwriter David S. Goyer looked to Dramatica for help or not, that natural balance within the story is there.

Perhaps they found it as a result of writing stories with similar thematic intent. Maybe the first came out a little rough, but as they continued to explore this area and refine their understandings of it, their intuition kicked in and assured a proper balance between the Throughlines. Dramatica is built on the psychology of the mind, not on observable repeated patterns within film. It only makes sense then that a theory based on the psychology of the human mind would be able to predict the intuition of a writer trying to construct a well-balanced story.

Something More Than Backstory

The confusion involved in locating the storyform for Batman Begins can be attributed to the use of time-shifting in the StoryWeaving phase. What looks like backstory is really an essential part of Bruce Wayne's growth as a Main Character. In next week's article we will continue to dive into the storyform for Batman Begins and explain how the mechanism of its narrative works.

This article originally appeared on Jim's Narrative First website. Hundreds of insightful articles, like this one, can be found in the Article Archives. Want to learn how to generate story ideas the way explained this article? Join our Dramatica® Mentorship Program and receive personalized instruction on how to master the Dramatica theory. Become a master storyteller. Learn more.

From there, Dramatica begins to work its magic and predicts story elements not selected. For Ra's Issue of Interdiction to work, Bruce himself must be facing an Issue of Suspicion. The suspicion that he had something to do with the murder of his family, and the suspicion that he is somewhat like his father–who also failed to act.

For Ra's Concern of the Past to work (which is forced by our selection of the Issue of Interdiction) then Bruce's Concern must have something to do with Memories. Anytime he steps out of his role as billionaire vigilante and confronts his own demons, they always have something to do with suppressed Memories.

The magic of Dramatica is simply balance. If an Influence Character looks to the Past, then a Main Character must look to their Memories. If an Influence Character looks to Intercede, then a Main Character must look to their own Suspicions. Whether Christopher Nolan or screenwriter David S. Goyer looked to Dramatica for help or not, that natural balance within the story is there.

Perhaps they found it as a result of writing stories with similar thematic intent. Maybe the first came out a little rough, but as they continued to explore this area and refine their understandings of it, their intuition kicked in and assured a proper balance between the Throughlines. Dramatica is built on the psychology of the mind, not on observable repeated patterns within film. It only makes sense then that a theory based on the psychology of the human mind would be able to predict the intuition of a writer trying to construct a well-balanced story.

Something More Than Backstory

The confusion involved in locating the storyform for Batman Begins can be attributed to the use of time-shifting in the StoryWeaving phase. What looks like backstory is really an essential part of Bruce Wayne's growth as a Main Character. In next week's article we will continue to dive into the storyform for Batman Begins and explain how the mechanism of its narrative works.

This article originally appeared on Jim's Narrative First website. Hundreds of insightful articles, like this one, can be found in the Article Archives. Want to learn how to generate story ideas the way explained this article? Join our Dramatica® Mentorship Program and receive personalized instruction on how to master the Dramatica theory. Become a master storyteller. Learn more.

Finding Your True Self Through Writing

June 2016

Going with your first impression is usually a recipe for disaster when it comes to writing. Far too many times, the first thing we come up with is simply a rehash of something we have already seen or read. Pushing ourselves to move beyond our comfort zone opens up worlds of story we never even knew we had inside.

Following up on last month's article Generating an Abundance of Story Ideas, we take a look at the remaining three Playground Exercises. To recap, I was struggling to come up with concrete imaginative encodings for my Influence Character's Story Points. Instead of using Dramatica's insights to make my story bigger, I was simply parroting the different appreciations and making my story smaller in the process. I eventually decided to take my own advice and began working through a series of Playground Exercises that I created to help clients break through their usual creative ruts.

The effect was staggering and I felt it would be good to share my experience with writers and producers wondering how to use Dramatica to increase their level of creativity.

New Discoveries

Note how different these three are from the previous two and how far away I started to get from my original story idea. This is a very good thing. Instead of writing a story that was already in my head and–let's be honest–not particularly original, I started to head down a path that reflected more of my subconscious thoughts & desires rather than the subconscious of someone else.

By locking in the thematic meaning of the story with the storyform, I was able to stretch my imagination with the confidence that I wasn't wasting my time. I wasn't heading down another blind alleys I wasn't wasting my precious few hours a day writing chasing the wrong dog.

With Marissa I found a character who found peace shutting out the world around her. With the Bonaporte family I found the pain induced by trying to keep the memory of a family member alive. With Harold I found gold.

Getting Personal

Now Harold is about as far away from my original Stephen King-inspired story idea that I could get: a character who was so deathly afraid of factory-style work because of it hid the reality of one's true calling. That should feel authentic to you, more authentic than the guy who couldn't remember if he killed someone, and it should–because it is something very honest and true to my heart.

I had no idea deep down inside that this is what I felt. I mean, I knew it on a superficial level, but I didn't know my true feelings on the subject. By working through these Playground Exercises I was able to unearth something extremely personal to me–something honest and real. Something that I could really dive into and communicate from deep within my own consciousness and experience.

I almost left this last one out. It's a bit too revelatory and I was concerned about what my colleagues in the animation industry might think of my true feelings. But I guarantee many of them feel the same–as do many of you. We've all had jobs or careers that didn't sit right, didn't feel authentic. And by getting to that honesty my story will now end up connecting more deeply with those who read or see it.

People go to stories for truth, for shared experiences. By not concerning myself with thematic intention or this character's relation to the rest of the story, I ended up forming someone who reflected my deepest of intentions. What writer wouldn't want that?

Next week I'll cover the process of folding these five very different characters into one. You can pretty much be guaranteed that Harold will fit predominantly into that mix.

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #3

Influence Character Domain & Concern

Hating People Who Whine & Being Forgotten by a Particular Group: Marissa Lamont is the kind of mother who hates when her children whine. So much so, that she will lock herself in her room, put noise-cancelling headphones on, and turn up the Anthrax until she can't hear it anymore. As a result, her children never learn to get along, the house is a battleground, and her hearing is shot. But there is something else…peace. That peace of mind she feels infects the other women in the neighborhood and they too begin to revel in the ecstasy of shutting everyone out. Husbands neglected, children undisciplined, and a general sense of breakdown of communications between people begins to occur. Marissa, and the women in her circle, want to be forgotten by those who demand so much from them. It causes those around her to feel deprived, uncared for, and ignored. But it also has the side effect of developing self-reliance in those she left behind. On the surface Lamont's influence is a disruptive element, but like most disruptive elements eventually turns to a beneficial and uplifting experience.

Influence Character Issue

Being a Source of Suspicion vs. Evidence: Marissa's antics are a source of suspicion amongst her fellow neighbors: what does she do behind those closed doors and what is she hiding from? That suspicion infects the neighborhood with gossip and distraction and a general lack of purpose as everyone finds themselves more interested in what Marissa is doing rather than what they should be doing (like paying bills, feeding the kids, and getting enough sleep for the next day).

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Philosophically Aligned with Something & Being Lost in Reverie about a Particular Group: Marissa believes the problem with most mothers these days is their philosophical alignment with suburban mores. Everyone is too caught up in aligning themselves with this idea of who they should be, rather than who they could be. Her response, and the response she has for so many of the women, is to become lost in reverie about long lost dreams, about that group of women they had planned to be as they were growing up. The only way to move past what you should be is to lose yourself in the dreams of what you used to want to be…

Influence Character Source of Drive

Seeing if Someone Truly Exists: Marissa Lamont is driven to see if this perfect suburban mother exists. She seeks her out in Internet chat rooms, in the grocery store, and even at school functions. Whenever she finds a woman she figure is the perfect woman, she approaches and begins breaking her down, asking insinuating questions and getting to the root of what that woman is really all about. Is she wearing that workout outfit because she is going to the gym as the perfect woman, or because she thinks she is supposed to be wearing a workout outfit to fit in. That drive to find what really exists cuts through the facade of suburban life and exposes these women for who they really are: hurt and put upon.

Influence Character DemotivatorCamouflaging a Particular Group: Even Marissa from time to time feels she has to hide and camouflage herself from her husband and her children, and when she does put on airs she manages to demotivate the other women around her and lessen her impact on the neighborhood.

Influence Character Benchmark

Reasoning: The more her children and husband try to reason with her, the more she grows concerned with the fact that they will never forget about her. That she will always be needed, and that she will never be able to live her dreams out. Communicating this to the other women allows them to see that simple reason will make it impossible for any of them to be forgotten.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Being Contemplative: When we first meet Marissa, she is at the head of the dinner table, children screaming, husband on his smart phone, expletives and food flying, a meal uneaten in front of her. Her daughter asks her a question and she seems distractive. “Just thinking, dear,” she tells her and returns back to her contemplation of the mashed potatoes in front of her. The contemplation confuses and intrigues her neighbor from down the street who stopped by for a drink. Marissa seems at such peace. “What is your secret?” She asks.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Having a Photographic Memory: Marissa inspires all the mothers around her when she begins to recite—from photographic memory—the exact imagery of each and every one of her children and even when her and her husband began first dating. The images play on the big screen TV, but Marissa has seen them all. Contrary to what the other husbands say about Marissa's strange behavior she hasn't forgotten or neglected her family—she remembers each and every detail about them. This inspires the women to return home and do the same.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Gagging at the Thought of Eating Oysters: The families arrive for a community cookout, a meal prepared by the husbands and by the children. The fathers present oysters to the women and Marissa begins gagging. Uncontrollably. It shocks and dismays everyone around them, but soon the other mothers turn away in disgust. It simply isn't good enough for them. Marissa shows them how to stand up for what you want, and to have that confidence that you deserve more.

Influence Character Signpost 4

Experiencing Rapture: The women of the neighborhood experience pure bliss as they shut out the world around them and indulge in their own personal happiness. Seventh heaven (the name of this story) kicks in as the women find peace refusing to compromise on their principals. Marissa reaches over, turns the knob on the Volume up to 10, and leans back in her chair and thinks to herself, “This is the life.”

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #4Influence Character Domain & ConcernClashing Attitudes about Someone & Losing Something's Memories: Lilly Bonaparte grew up in a household centered around the patriarch of the family, Edward G. Bonaparte V. Treated like royalty his whole life, Edward had problem keeping his family in line and on track with his wishes and plans. Everyone that is…except Lily. At 13 she couldn't stand the old man and did whatever she could to disrupt their perfect little family. She would refuse to pray before dinner, refuse to do chores, refuse to come home before curfew, refuse to not date anyone older than her, and refuse to contribute in any meaningful way to the family. Suffice it to say, Lilly Bonaparte's attitudes towards her father angered him, brought anxiety to her mother, and threw the rest of her five siblings into constant brawls over who would take up her slack. At the heart of Lilly's concerns were the loss of the memory of Edward's mother, Valerie. Valerie was in the last stages of Parkinson's disease and was on the brink of losing all touch with reality—a travesty as far as far Lilly was concerned. And the idea that her father never visited Valerie or made any attempts to collect her memoirs or family's history devastated Lilly and drove her to label her father a miserable son who would only beget more miserable children and grandchildren. Effectively cursing the entire family lineage, Lilly brought turmoil and angst to the Bonaparte household with her efforts to keep Valerie and her more lenient ways of parenting alive.

Influence Character Issue

Being Suspicious of Someone vs. Evidence: Lilly's suspicion that father was doing all of this as a means of guaranteeing a larger inheritance only drove her to sneak into the old man's study and rifle through his things, hack into his computer, and reveal family secrets kept secret for a long time (like who was brother Austin's real mother). This suspicious attitude brought dissention and grief to the Bonaparte household and upset the tender balance Edward had worked his whole life to maintain.

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Known by a Particular Group & Brainstorming Something: Lilly believes the problem to be that the Bonaparte's are known as a perfect family, something to aspire to, and to look up to by the other families. This is, of course, a problem as their family is completely built on lies and the ego of one man. In response, Lilly works hard to brainstorm different means of bringing her father down—an approach that unnerves the other children, incites some of the others to rebel and talk back to their father, and begins a wave of rumors throughout their tightly knit neighborhood of friends.

Influence Character Source of Drive

Exploring Reality: Lilly's drive to explore the reality behind the Bonaparte family and Edward's real life growing up brings turmoil to the Bonaparte household. Let sleeping dogs lie is not something Lilly believes in and as a result the tender bond between Edward and Valerie is forever shattered, reducing the family inheritance, and bringing shame and embarrassment to the Bonaparte family in the eyes of the other neighbors. It, however, also has the positive effect of inspiring her siblings to stand up on their own and claim their own individuality within the family—a disruptive effect in the eyes of the patriarch, but a positive move from those oppressed by his ways.

Influence Character Demotivator

Seeing Someone from a Particular Perspective: When her siblings begin seeing their father in a different light, Lilly tends to back off, her mission accomplished.

Influence Character Benchmark

Considering Something: The more her siblings consider that their father is not the great man he makes himself out to be, the less concerned Lilly is with losing her grandmother's experiences…the other kids will see to it that no one forgets.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Being Conscious of Something: Lilly starts the story by making everyone in her family conscious of her father's affair seven years ago. Out of nowhere. No one was even talking about it, Lilly just interjected between Roger and Mary's stimulating conversation about the difference between stalactites and stalagmites. “You all know dear old father had an affair with Miss Torio seven years ago, don't you?” That one comment set off a wave of disappointment and chaos.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Thinking Back about a Particular Group: Lilly takes her three oldest brothers out on a hike and strikes up a conversation about how the Bonapartes used to be back in the day. She wonders if they can think back and remember how it was before Valerie became old and decrepit and if they recall a time when the family was more about joy and expression than it was about following rules and decorum. The boys do recall. One, Andrew the oldest, gets really upset and refuses to talk about it anymore. He heads home angered. The other two recall and promise Lilly to tell the others when they get back.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Reacting Spontaneously to Someone: Edward loses his cool in front of everyone when out to dinner. Lilly demands that an extra chair be set for Valerie, even though she can't make it, and that sends Edward over the edge. In front of his wife, his family, and the rest of the neighborhood in attendance at Dolario's, Edward flips out and starts cursing the very existence of Lilly. She simply sits back and smiles. “At least, “ she says. “My real father shows up.”

Influence Character Signpost 4

Being Infatuated with a Particular Group: The local reporter, a man in the booth next to the Bonapartes at Dolario's, becomes infatuated with the family and sets out to write the family's memoir—exposing Edward for the sniveling son he is and the abuse some children engage in towards aging and disabled parents. The reporters expose is met with unrivaled acclaim and soon the Bonaparte name becomes synonymous with parental abuse, particularly in the case of Parkinson's. The Bonaparte name is forever memorialized as something you would never want to associate your own family with.

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #5

Influence Character Domain & Concern

Fearing Work & Remembering an Anniversary: Harold Fauntleroy is deathly afraid of work. Why commit yourself to a task you would never do if they didn't pay you? That is not what life is about, that's voluntary slavery! Unfortunately for Harold's wife and two sons his fear keeps them homeless, hungry, and hopeless. His wife must take on an extra job and her sons are left to fend for themselves while their parents are away. Of great concern to Harold is the anniversary of his father's passing away, which is coming up in a few weeks. His father never lived his life, never took a chance, and always did everything the way he was told to. As a result he died content…but an unhappy content. Harold remembers the look on his father's face when he told Harold his life was a waste and that look of emptiness scares Harold so much that he refuses to commit to anything lasting longer than a week or two. The Fauntleroys struggle as winter approaches and the thought of sleeping in their car becomes more and more a reality.

Influence Character Issue

Being Paranoid about Someone vs. Evidence: Harold's constant paranoia that his employer is trying to diminish his soul creates an uneasy work environment for those who work with him and inspires others to quit or possibly do less work so that they too can concentrate on their own art. The paranoia—while disruptive to those in charge—actually inspires great things in others. A woman who hadn't picked up a paint brush in 35 years begins painting her cubicle walls. A man who always wrote short stories begins taking afternoons off at the office to work on his masterpiece. Harold Fauntleroy brings out the best in others by being paranoid about the truth of those in charge.

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Ignorant & Considering Someone: Harold believes the biggest problem in the world is when people are ignorant. Ignorant of what is really going on around them and ignorant of what it is their heart truly desires. Harold sits down with each and every person and tells them that he considers them special. That he thinks about them. That he sees a unique individual capable of doing a great many things. The only thing they need to do is to get other people to start considering them. That's when they know they are on the right track.

Influence Character Source of Drive

Finding the Objective Reality of Someone: What excites Harold is finding the objective reality of the people he meets. Everyone he meets is hiding behind a mask, a false sense of themselves. Unearthing that truth, that reality that is there deep within each person unnerves those who have never stepped out of their comfort zone, and excites those who have dreamt of being so much more. Harold is all about reality. It may drive his wife crazy and his kids to become more fearful about what is happening with their family, but Harold is doing good work. He's bringing light to the world.

Influence Character Demotivator

Having a Slanted View on Something: Unfortunately, Harold's wife has her viewpoint on things and it does diminish his effectiveness from time to time. As committed as he is to truth, he does love his wife and hates to see her so nervous and anxious. Her slanted view on life and doing what others expect of you tempers Harold's drive and pulls him back occasionally from making huge gains.

Influence Character Benchmark

Considering Something: The more people consider doing something they have never done before, the less concerned Harold is with the anniversary of his father's death. It means there was a purpose behind it.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Starting a Think Tank: Harold begins to disrupt the universe the moment he requests a meeting room at work and begins to develop a think tank for creative endeavors. Inspired by Google's 5th day of personal projects, Harold starts brainstorming with the other employees how they too could make something more of themselves. This think tank upsets the employers, drives down productivity, and frightens stock holders. But it inspires the workers.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Thinking Back about Something: Harold pushes it farther when he gets those workers to begin to think back to when they were children and when they had dreams and no limitations. When the future seemed boundless. This thinking back inspires some of the workers—essential to the company's success-to quit to go follow their dreams. Harold is brought in and fired for his disruptive behavior.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Being Numb to Something: Harold's former employees act numb to threats from their employer. When brought in to a meeting to set rules and expectations and threats of firing, they act as if numb to the entire thing. Their heads are already in the clouds because of Harold and no amount of threat is ever going to change that.

Influence Character Signpost 4

Fearing Water: Fearing the rising tide of employee dissention created by Harold's persistent influence, the company decides to move its entire operation off-shore. Everyone is fired, but not a single person fears the consequences. They get in touch with Harold and he begins a new company—one that offers a chance for everyone to fulfill their true potential. In time, they all fulfill their greatest desires.

This article originally appeared on Jim's Narrative First website. Hundreds of insightful articles, like this one, can be found in the Article Archives. Want to learn how to generate story ideas the way explained this article? Join our Dramatica Mentorship Program and receive personalized instruction on how to master the Dramatica theory. Become a master storyteller. Learn more.

June 2016

Going with your first impression is usually a recipe for disaster when it comes to writing. Far too many times, the first thing we come up with is simply a rehash of something we have already seen or read. Pushing ourselves to move beyond our comfort zone opens up worlds of story we never even knew we had inside.

Following up on last month's article Generating an Abundance of Story Ideas, we take a look at the remaining three Playground Exercises. To recap, I was struggling to come up with concrete imaginative encodings for my Influence Character's Story Points. Instead of using Dramatica's insights to make my story bigger, I was simply parroting the different appreciations and making my story smaller in the process. I eventually decided to take my own advice and began working through a series of Playground Exercises that I created to help clients break through their usual creative ruts.

The effect was staggering and I felt it would be good to share my experience with writers and producers wondering how to use Dramatica to increase their level of creativity.

New Discoveries

Note how different these three are from the previous two and how far away I started to get from my original story idea. This is a very good thing. Instead of writing a story that was already in my head and–let's be honest–not particularly original, I started to head down a path that reflected more of my subconscious thoughts & desires rather than the subconscious of someone else.

By locking in the thematic meaning of the story with the storyform, I was able to stretch my imagination with the confidence that I wasn't wasting my time. I wasn't heading down another blind alleys I wasn't wasting my precious few hours a day writing chasing the wrong dog.

With Marissa I found a character who found peace shutting out the world around her. With the Bonaporte family I found the pain induced by trying to keep the memory of a family member alive. With Harold I found gold.

Getting Personal

Now Harold is about as far away from my original Stephen King-inspired story idea that I could get: a character who was so deathly afraid of factory-style work because of it hid the reality of one's true calling. That should feel authentic to you, more authentic than the guy who couldn't remember if he killed someone, and it should–because it is something very honest and true to my heart.

I had no idea deep down inside that this is what I felt. I mean, I knew it on a superficial level, but I didn't know my true feelings on the subject. By working through these Playground Exercises I was able to unearth something extremely personal to me–something honest and real. Something that I could really dive into and communicate from deep within my own consciousness and experience.

I almost left this last one out. It's a bit too revelatory and I was concerned about what my colleagues in the animation industry might think of my true feelings. But I guarantee many of them feel the same–as do many of you. We've all had jobs or careers that didn't sit right, didn't feel authentic. And by getting to that honesty my story will now end up connecting more deeply with those who read or see it.

People go to stories for truth, for shared experiences. By not concerning myself with thematic intention or this character's relation to the rest of the story, I ended up forming someone who reflected my deepest of intentions. What writer wouldn't want that?

Next week I'll cover the process of folding these five very different characters into one. You can pretty much be guaranteed that Harold will fit predominantly into that mix.

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #3

Influence Character Domain & Concern

Hating People Who Whine & Being Forgotten by a Particular Group: Marissa Lamont is the kind of mother who hates when her children whine. So much so, that she will lock herself in her room, put noise-cancelling headphones on, and turn up the Anthrax until she can't hear it anymore. As a result, her children never learn to get along, the house is a battleground, and her hearing is shot. But there is something else…peace. That peace of mind she feels infects the other women in the neighborhood and they too begin to revel in the ecstasy of shutting everyone out. Husbands neglected, children undisciplined, and a general sense of breakdown of communications between people begins to occur. Marissa, and the women in her circle, want to be forgotten by those who demand so much from them. It causes those around her to feel deprived, uncared for, and ignored. But it also has the side effect of developing self-reliance in those she left behind. On the surface Lamont's influence is a disruptive element, but like most disruptive elements eventually turns to a beneficial and uplifting experience.

Influence Character Issue

Being a Source of Suspicion vs. Evidence: Marissa's antics are a source of suspicion amongst her fellow neighbors: what does she do behind those closed doors and what is she hiding from? That suspicion infects the neighborhood with gossip and distraction and a general lack of purpose as everyone finds themselves more interested in what Marissa is doing rather than what they should be doing (like paying bills, feeding the kids, and getting enough sleep for the next day).

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Philosophically Aligned with Something & Being Lost in Reverie about a Particular Group: Marissa believes the problem with most mothers these days is their philosophical alignment with suburban mores. Everyone is too caught up in aligning themselves with this idea of who they should be, rather than who they could be. Her response, and the response she has for so many of the women, is to become lost in reverie about long lost dreams, about that group of women they had planned to be as they were growing up. The only way to move past what you should be is to lose yourself in the dreams of what you used to want to be…

Influence Character Source of Drive

Seeing if Someone Truly Exists: Marissa Lamont is driven to see if this perfect suburban mother exists. She seeks her out in Internet chat rooms, in the grocery store, and even at school functions. Whenever she finds a woman she figure is the perfect woman, she approaches and begins breaking her down, asking insinuating questions and getting to the root of what that woman is really all about. Is she wearing that workout outfit because she is going to the gym as the perfect woman, or because she thinks she is supposed to be wearing a workout outfit to fit in. That drive to find what really exists cuts through the facade of suburban life and exposes these women for who they really are: hurt and put upon.

Influence Character DemotivatorCamouflaging a Particular Group: Even Marissa from time to time feels she has to hide and camouflage herself from her husband and her children, and when she does put on airs she manages to demotivate the other women around her and lessen her impact on the neighborhood.

Influence Character Benchmark

Reasoning: The more her children and husband try to reason with her, the more she grows concerned with the fact that they will never forget about her. That she will always be needed, and that she will never be able to live her dreams out. Communicating this to the other women allows them to see that simple reason will make it impossible for any of them to be forgotten.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Being Contemplative: When we first meet Marissa, she is at the head of the dinner table, children screaming, husband on his smart phone, expletives and food flying, a meal uneaten in front of her. Her daughter asks her a question and she seems distractive. “Just thinking, dear,” she tells her and returns back to her contemplation of the mashed potatoes in front of her. The contemplation confuses and intrigues her neighbor from down the street who stopped by for a drink. Marissa seems at such peace. “What is your secret?” She asks.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Having a Photographic Memory: Marissa inspires all the mothers around her when she begins to recite—from photographic memory—the exact imagery of each and every one of her children and even when her and her husband began first dating. The images play on the big screen TV, but Marissa has seen them all. Contrary to what the other husbands say about Marissa's strange behavior she hasn't forgotten or neglected her family—she remembers each and every detail about them. This inspires the women to return home and do the same.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Gagging at the Thought of Eating Oysters: The families arrive for a community cookout, a meal prepared by the husbands and by the children. The fathers present oysters to the women and Marissa begins gagging. Uncontrollably. It shocks and dismays everyone around them, but soon the other mothers turn away in disgust. It simply isn't good enough for them. Marissa shows them how to stand up for what you want, and to have that confidence that you deserve more.

Influence Character Signpost 4

Experiencing Rapture: The women of the neighborhood experience pure bliss as they shut out the world around them and indulge in their own personal happiness. Seventh heaven (the name of this story) kicks in as the women find peace refusing to compromise on their principals. Marissa reaches over, turns the knob on the Volume up to 10, and leans back in her chair and thinks to herself, “This is the life.”

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #4Influence Character Domain & ConcernClashing Attitudes about Someone & Losing Something's Memories: Lilly Bonaparte grew up in a household centered around the patriarch of the family, Edward G. Bonaparte V. Treated like royalty his whole life, Edward had problem keeping his family in line and on track with his wishes and plans. Everyone that is…except Lily. At 13 she couldn't stand the old man and did whatever she could to disrupt their perfect little family. She would refuse to pray before dinner, refuse to do chores, refuse to come home before curfew, refuse to not date anyone older than her, and refuse to contribute in any meaningful way to the family. Suffice it to say, Lilly Bonaparte's attitudes towards her father angered him, brought anxiety to her mother, and threw the rest of her five siblings into constant brawls over who would take up her slack. At the heart of Lilly's concerns were the loss of the memory of Edward's mother, Valerie. Valerie was in the last stages of Parkinson's disease and was on the brink of losing all touch with reality—a travesty as far as far Lilly was concerned. And the idea that her father never visited Valerie or made any attempts to collect her memoirs or family's history devastated Lilly and drove her to label her father a miserable son who would only beget more miserable children and grandchildren. Effectively cursing the entire family lineage, Lilly brought turmoil and angst to the Bonaparte household with her efforts to keep Valerie and her more lenient ways of parenting alive.

Influence Character Issue

Being Suspicious of Someone vs. Evidence: Lilly's suspicion that father was doing all of this as a means of guaranteeing a larger inheritance only drove her to sneak into the old man's study and rifle through his things, hack into his computer, and reveal family secrets kept secret for a long time (like who was brother Austin's real mother). This suspicious attitude brought dissention and grief to the Bonaparte household and upset the tender balance Edward had worked his whole life to maintain.

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Known by a Particular Group & Brainstorming Something: Lilly believes the problem to be that the Bonaparte's are known as a perfect family, something to aspire to, and to look up to by the other families. This is, of course, a problem as their family is completely built on lies and the ego of one man. In response, Lilly works hard to brainstorm different means of bringing her father down—an approach that unnerves the other children, incites some of the others to rebel and talk back to their father, and begins a wave of rumors throughout their tightly knit neighborhood of friends.

Influence Character Source of Drive

Exploring Reality: Lilly's drive to explore the reality behind the Bonaparte family and Edward's real life growing up brings turmoil to the Bonaparte household. Let sleeping dogs lie is not something Lilly believes in and as a result the tender bond between Edward and Valerie is forever shattered, reducing the family inheritance, and bringing shame and embarrassment to the Bonaparte family in the eyes of the other neighbors. It, however, also has the positive effect of inspiring her siblings to stand up on their own and claim their own individuality within the family—a disruptive effect in the eyes of the patriarch, but a positive move from those oppressed by his ways.

Influence Character Demotivator

Seeing Someone from a Particular Perspective: When her siblings begin seeing their father in a different light, Lilly tends to back off, her mission accomplished.

Influence Character Benchmark

Considering Something: The more her siblings consider that their father is not the great man he makes himself out to be, the less concerned Lilly is with losing her grandmother's experiences…the other kids will see to it that no one forgets.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Being Conscious of Something: Lilly starts the story by making everyone in her family conscious of her father's affair seven years ago. Out of nowhere. No one was even talking about it, Lilly just interjected between Roger and Mary's stimulating conversation about the difference between stalactites and stalagmites. “You all know dear old father had an affair with Miss Torio seven years ago, don't you?” That one comment set off a wave of disappointment and chaos.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Thinking Back about a Particular Group: Lilly takes her three oldest brothers out on a hike and strikes up a conversation about how the Bonapartes used to be back in the day. She wonders if they can think back and remember how it was before Valerie became old and decrepit and if they recall a time when the family was more about joy and expression than it was about following rules and decorum. The boys do recall. One, Andrew the oldest, gets really upset and refuses to talk about it anymore. He heads home angered. The other two recall and promise Lilly to tell the others when they get back.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Reacting Spontaneously to Someone: Edward loses his cool in front of everyone when out to dinner. Lilly demands that an extra chair be set for Valerie, even though she can't make it, and that sends Edward over the edge. In front of his wife, his family, and the rest of the neighborhood in attendance at Dolario's, Edward flips out and starts cursing the very existence of Lilly. She simply sits back and smiles. “At least, “ she says. “My real father shows up.”

Influence Character Signpost 4

Being Infatuated with a Particular Group: The local reporter, a man in the booth next to the Bonapartes at Dolario's, becomes infatuated with the family and sets out to write the family's memoir—exposing Edward for the sniveling son he is and the abuse some children engage in towards aging and disabled parents. The reporters expose is met with unrivaled acclaim and soon the Bonaparte name becomes synonymous with parental abuse, particularly in the case of Parkinson's. The Bonaparte name is forever memorialized as something you would never want to associate your own family with.

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding #5

Influence Character Domain & Concern

Fearing Work & Remembering an Anniversary: Harold Fauntleroy is deathly afraid of work. Why commit yourself to a task you would never do if they didn't pay you? That is not what life is about, that's voluntary slavery! Unfortunately for Harold's wife and two sons his fear keeps them homeless, hungry, and hopeless. His wife must take on an extra job and her sons are left to fend for themselves while their parents are away. Of great concern to Harold is the anniversary of his father's passing away, which is coming up in a few weeks. His father never lived his life, never took a chance, and always did everything the way he was told to. As a result he died content…but an unhappy content. Harold remembers the look on his father's face when he told Harold his life was a waste and that look of emptiness scares Harold so much that he refuses to commit to anything lasting longer than a week or two. The Fauntleroys struggle as winter approaches and the thought of sleeping in their car becomes more and more a reality.

Influence Character Issue

Being Paranoid about Someone vs. Evidence: Harold's constant paranoia that his employer is trying to diminish his soul creates an uneasy work environment for those who work with him and inspires others to quit or possibly do less work so that they too can concentrate on their own art. The paranoia—while disruptive to those in charge—actually inspires great things in others. A woman who hadn't picked up a paint brush in 35 years begins painting her cubicle walls. A man who always wrote short stories begins taking afternoons off at the office to work on his masterpiece. Harold Fauntleroy brings out the best in others by being paranoid about the truth of those in charge.

Influence Character Symptom & Response

Being Ignorant & Considering Someone: Harold believes the biggest problem in the world is when people are ignorant. Ignorant of what is really going on around them and ignorant of what it is their heart truly desires. Harold sits down with each and every person and tells them that he considers them special. That he thinks about them. That he sees a unique individual capable of doing a great many things. The only thing they need to do is to get other people to start considering them. That's when they know they are on the right track.

Influence Character Source of Drive

Finding the Objective Reality of Someone: What excites Harold is finding the objective reality of the people he meets. Everyone he meets is hiding behind a mask, a false sense of themselves. Unearthing that truth, that reality that is there deep within each person unnerves those who have never stepped out of their comfort zone, and excites those who have dreamt of being so much more. Harold is all about reality. It may drive his wife crazy and his kids to become more fearful about what is happening with their family, but Harold is doing good work. He's bringing light to the world.

Influence Character Demotivator

Having a Slanted View on Something: Unfortunately, Harold's wife has her viewpoint on things and it does diminish his effectiveness from time to time. As committed as he is to truth, he does love his wife and hates to see her so nervous and anxious. Her slanted view on life and doing what others expect of you tempers Harold's drive and pulls him back occasionally from making huge gains.

Influence Character Benchmark

Considering Something: The more people consider doing something they have never done before, the less concerned Harold is with the anniversary of his father's death. It means there was a purpose behind it.

Influence Character Signpost 1

Starting a Think Tank: Harold begins to disrupt the universe the moment he requests a meeting room at work and begins to develop a think tank for creative endeavors. Inspired by Google's 5th day of personal projects, Harold starts brainstorming with the other employees how they too could make something more of themselves. This think tank upsets the employers, drives down productivity, and frightens stock holders. But it inspires the workers.

Influence Character Signpost 2

Thinking Back about Something: Harold pushes it farther when he gets those workers to begin to think back to when they were children and when they had dreams and no limitations. When the future seemed boundless. This thinking back inspires some of the workers—essential to the company's success-to quit to go follow their dreams. Harold is brought in and fired for his disruptive behavior.

Influence Character Signpost 3

Being Numb to Something: Harold's former employees act numb to threats from their employer. When brought in to a meeting to set rules and expectations and threats of firing, they act as if numb to the entire thing. Their heads are already in the clouds because of Harold and no amount of threat is ever going to change that.

Influence Character Signpost 4

Fearing Water: Fearing the rising tide of employee dissention created by Harold's persistent influence, the company decides to move its entire operation off-shore. Everyone is fired, but not a single person fears the consequences. They get in touch with Harold and he begins a new company—one that offers a chance for everyone to fulfill their true potential. In time, they all fulfill their greatest desires.

This article originally appeared on Jim's Narrative First website. Hundreds of insightful articles, like this one, can be found in the Article Archives. Want to learn how to generate story ideas the way explained this article? Join our Dramatica Mentorship Program and receive personalized instruction on how to master the Dramatica theory. Become a master storyteller. Learn more.

Generating an Abundance of Story Ideas

May 2016

Too many times writers find themselves stuck without an inkling of where to go next. They write themselves into corners or run out of steam on that great idea that they thought would carry them through the end. Having an understanding of what it is you want to say and a framework for capturing that intent can go a long way towards preventing what many call writer's block.

Many see the Dramatica theory of story as a great analysis tool, something to be used to examine what worked and what didn't work. What they fail to realize is that Dramatica is also a great creativity tool. By listening to what it is you want to say with your story, Dramatica can offer insight and suggestions to round out your story and make it feel more complete.

The Playground ExercisesYou know that writing tip that suggests coming up with twenty different ideas in order to get to one original one? The idea being that your first, your fifth, and even your fifteenth idea is really just a superficial rehash of something you have already seen or have already thought. Once you vomit out all the obvious choices your writer's intuition starts coming up with brand new and novel ideas that take your writing to the next level.

The Narrative First Playground Exercises were inspired by this process. The generation of several different Throughlines with slightly different storytelling grants an Author a playground from which to explore the deep thematic meaning present in their story. Even my own story.

My StoryWorking my way through the Playground Exercises for my current writing project, I was amazed by the abundance of creativity I experienced in only a few hours. Averaging about 25 minutes per Playground, I managed to flesh out five completely different and potential Influence Characters for my story. That's five fully functional and thematically integrated characters all before lunchtime.

Sounds exciting, right?

Inspired by something Dramatica co-creator Chris Huntley mentioned to me, I created the Playground Exercises late last Summer as a means to better understand the Main Character in the story I was working on. I was continuously running into a roadblock with this character and couldn't figure out why she seemed so small in comparison to the rest of the story.

By brainstorming ideas for characters dealing with the same thematic material as my Main Characters, I was able to concentrate on the essence of the Throughline–the meaty, thematic stuff–instead of futzing around wondering how it would fit into my story. The process was, and is, freeing and productive and often produces ideas for new and completely different stories.

There is a right way and a wrong way to do them and very often when working with clients they start out with the latter approach. This is a shared mistake brought about by the common misunderstanding that the Dramatica storyform presents storytelling material, rather than storyforming material.

The Storyform as a Source of ConflictMany look to Dramatica and think it is a story-by-numbers approach. They think you flip a few switches and Dramatica spits out a preformed story. When they see a Main Character Concern of the Past they think, Oh, Roger is worried about the Past. or when they see a Main Character Problem of Feeling they think, Oh, Roger is the kind of person who feels a lot of mixed emotions.

This is not proper StoryEncoding. This is using the Appreciation as storytelling, rather than using it as a means to form a story.

A Main Character Concern of the Past means the Main Character experiences conflict because of the Past. Sure, he or she may be worried about the Past, but this worry doesn't set into motion a story. Instead, a Main Character who is so concerned with how great things used to be that they return to their high-school summer job at 42, start working out how to impress their teenage daughter's girlfriend, and start buying drugs from the neighbor next door to feel young again DOES set a story into motion. In fact, it sounds an awful lot like American Beauty doesn't it? Kevin Spacey's character Lester Burnham does have a Concern of the Past, but it's more than an indicator of worry, it's a generator of conflict.

Likewise, a Main Character Problem of Feeling means the Main Character experiences conflict because of Feeling. Of course this means they will "feel a lot of mixed emotions" but then again, what kind of character doesn't? Instead, a Main Character who is so overwhelmed by strange and uncomfortable emotions that they will pummel anyone who brings those emotions out DOES set a story into motion. In fact this was the problem Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) suffered in Brokeback Mountain. His inability to process his Feelings with the evidence he had of the torture and murder of a man who embraced similar emotions drove him to a life spent in denial and personal anguish.

This is the first rule of the Playground Exercises: Do not use the Appreciation (or Gist) as storytelling, but rather as a source of conflict.

Looking for Conflict in the Right ThroughlineOne should always look to each of these appreciations and ask, How is this a problem? While they have fancy names like Domain and Concern and Issue, really they're just different magnifications of the same thing: conflict. The Domain is the largest, most broadest way to describe an area of conflict; the Concern is the next smallest and the Issue even smaller. The Problem is the smallest way to describe a Problem (can't go much smaller than that!).

So when working through these appreciations and random Gists I simply ask myself, How is this a source of conflict for this Throughline? Each Throughline will have a slightly different question. The Main Character is very experiential and personal and typically the easiest to write. In contrast, the Influence Character is all about the impact or influence that character has on the world around them. When writing these I always made sure to write a character who created all kinds of havoc around them and for others because of who they were and what they were driven to do. This brings up the second rule.

The second rule when doing these Playground Exercises is to ignore the other Throughlines. Don't worry about them. I don't care one bit how the Influence Characters I come up with are going to impact the Main Character of my story because in the end, the storyform will make sure this character impacts the Main Character.

In my story the Main Character has a Concern of the Past and the Influence Character has a Concern of Memories. Right there, the impact is set. The Main Character in my story will naturally be impacted by this Influence Character because my Main Character is personally dealing with The Past–she can't help but be influenced by this strange thing known as "Memories".

Concentrate on getting the StoryEncoding strong for an Influence Character who impacts others through their Concern and the storyform will naturally impact the Main Character regardless of what you come up with.

Generating an Abundance of IdeasHow does this process work? This is the Influence Character Throughline section of my storyform for my latest project:

Influence Character Throughline

Domain: Fixed Attitude

Concern: Memories

Issue: Suspicion vs. Evidence

Problem: Actuality

Solution: Perception

Symptom: Knowledge

Response: Thought

Benchmark: Contemplations

Signpost 1: Contemplations

Signpost 2: Memories

Signpost 3: Impulsive Reponses

Signpost 4: Innermost Desires

I have no problem sharing this with you as no one really owns a storyform. How I interpret and encode a storyform will be completely different than the way you do. That's what makes us unique and awesome.

Originally I was really excited about this storyform because it perfectly matched up with my story idea: that of a friend who wakes up a murder suspect, yet has no recollection of what they did the night before. The storyform above looked perfect for what I wanted to do: a Concern of Memories (he couldn't remember what happened), an Issue of Suspicion (everyone suspected him of killing), a Problem of Actuality (he actually killed the person!)–all of these seemed to really work great for the story I wanted to tell.

But when I went to actually write the thing the story kind of collapsed in on itself. I kept repeating myself with the Influence Character and he came off as kind of one-dimensional. What was worse was that he really didn't have any kind of effect or impact on the Main Character–she changed her resolve because I needed her to for the story, not because this other character challenged her to do so.

I resisted and resisted and put off doing my own Playground Exercises because I figured I was above all that. After all, twenty years of experience with Dramatica I should know what I'm doing, right? Turns out, I was short-changing my own writing process. By refusing to do what I had seen work wonders so many times before, I was keeping myself from writing a thematically rich and compelling story.

So I generated five different Influence Character Throughlines with the same storyform you see above by using Dramatica's Brainstorming feature. With this feature you can lock in the storyform and then randomize the Gists, or approximation of the story points, to keep the storytelling fresh and unique. I copied them over into Quip–the same app I use to work with clients–and then began brainstorming completely different Influence Characters. Different situations. Different genres. Different genders. But at the heart of them–the same thematic concerns of narrative.

Here are two of them. Note how disparate in storytelling, yet similar in thematic intent, they are. Note how every appreciation generates conflict and doesn't use the Gist as simply a storytelling prompt. There are moments when I start out using it as storytelling, but then quickly move it into a source for conflict.

Note too how I start out writing something somewhat similar to my original idea. This is how the Playground Exercise works–it lets you dump out your first thoughts and then forces you to stretch and become something more than you were before you started. You know the old adage You can't solve a problem with the same mind that created it? That is precisely what we're doing here–transforming minds to become better writers.

You should be able to see the magic that is the Playground Exercises and of the Dramatica storyform for generating new and wonderful characters. In the next article I'll present more examples and explain how I take these exercises and use them to craft a fully fleshed out and developed character for my story.

Influence Character Throughline StoryEncoding Example #1Influence Character Domain & ConcernBeing in a Special Group & Reminiscing about Someone: Roger, a 16-year old autistic boy, challenges the people around him with his strange behavior and demanding personality. To know Roger is to constantly be on edge, always fearful of saying the wrong thing, and always careful to make sure his every need is met—even before he asks for it. The result is an uneasy environment around Roger; people rarely take risks if they fear repercussions and Roger is full of them.